Issues- Art Projects- Critical Conversations- Lectures- Journal Press- Contact- Home-

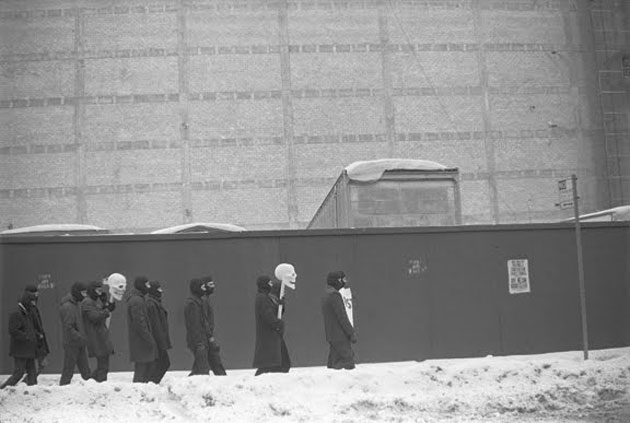

Black Mask on their way to lincoln center

On Hiatus"

The Imminent Impossibility of the Art Strike

- By Gabriel Mindel Saloman

#9

bios

buy

The following essay was originally written in the Fall of 2012 during a seminar led by Jin-me Yoon and co-facilitated by Gareth James, James Thornhill and Fulvia Carnavale at Simon Fraser University in Vancouver, BC, Unceded Coast Salish Territories. It has been partially updated for clarity and to offer further reference material discovered since it's initial completion, but is otherwise unchanged, even if my own thinking and world events are not. Thanks to the Lower Mainland Painting Co. for their initial inspiration and to the editors of the Journal of Aesthetics and Protest for their support.

The Art Strike in Context

The artistic "avant-garde" has always been associated with a radical attempt to transform society politically through formal and social interventions into art and its institutions.i These interventions have at times modeled themselves after political formations from other spheres in an attempt to reproduce similar structural reforms and to forge alliances between artists and other groups of radicalized subjects. A part of the larger project of eradicating the boundaries of art and life, these social practices have often found themselves wrapped up in the contradictions of the material practice of making art, engaging in what Peter Burger calls the "self-criticism" of art as an institution.ii They attack the institution of art as a means of restoring it to a demi-utopian moment where-in issues of social and economic justice and aesthetic concerns are both resolved. Though this may seem in practice to be an act of "anti-art" iconoclasm, it invariably finds its intensity in aspirations which none-the-less valorize art and artists. A quite literal example of this might be the last half-century's repeated conjuring of the "Art Strike" in which the artist withholds their labor as a means of critiquing, pressuring, reforming or even destroying the dominant apparatus' of the mainstream art-world.

The Art Strike is both an open ended potential and a specific artistic and social gesture which has appeared numerous times since its most famous 1970 iteration as the New York Art Strike Against Racism, War and Repression. There are concrete examples of artists attempting a form of boycott or a withholding of labour which both follow and predate this event, all of which have the general character of a strike, but only a small number explicitly identify as an "Art Strike". To clarify terms, I'll define a "strike" here and elsewhere as a suspension of normative behavior, in particular any form of labor, as a means towards some political end.iii Though the concept of a "strike" is almost always tied to the limited field of work/non-work, it is far more expansive a possibility when considered in terms of what anarchist-syndicalist Siegfried Nacht referred to as the "Social General Strike." Describing it in its "profoundest conception," Nacht viewed the Social General Strike as connoting "... a world social revolution; an entire new reorganization; a demolition of the entire old system..." which had the potential to spread to the "indolent masses who were dissatisfied and complained of their fate, but didn't have the courage to revolt" by means of an "energetic and enthusiastic minority" - i.e. an avant-garde.iv

Believing as Nacht did that "the example of the strike is, in fact, suggestive and contagious," numerous artists have attempted to test this theory within the field of their own labor. The specific nature or site of that labor, in other words its material structure or even the definition of "Art" itself, remains amorphous and without a consensus among artists, making the strike as a means of organizing individuals incredibly difficult. It is consistent across Art Strikes that the act is performed in opposition to forces which variously oppress the individual artist, their community or else attempts to conform art and artists to a process that favors (or even enables) institutions and the capitalist economic system. Yet the Art Strike is a wholly heterogeneous concept which in parallel with popular politics has steadily evolved to an evermore ambiguous and negative form.

I am interested in the question of how artists have historically attempted to reshape art and society through political intervention in the Art-world by means of the Art Strike. In this paper I will look at various Art Strikes as a means of constructing a provisional history and developing an understanding of both what the Art Strike is and what it yet may be. I will begin by addressing the contemporary shift in popular politics from what I call "Oriented" to "Disoriented" positions in order to provide a basis for understanding the distinctions between strikes. From this context I will look at a succession of self-articulated Art Strikes, providing history and some critical assessment of how each is enacted in relation to previous strategies. I will also consider contemporaneous and more current activities by artists which I believe also constitute a form of Art Strike but whose actions may not categorically identify with the concept. In conclusion I hope to offer not only substantial theoretical understanding of what the Art Strike in fact is, but propose what latent possibilities yet remain for this tactic to produce its desired effects.

Orientation and Disorientation

To understand the logic (or illogic) of the Art Strike we need to use a political language that allows for the multitude of problematics and contradictions which immediately mark it as "impossible." We can begin by acknowledging the vagueness and inaccuracy of any assumption that Art is automatically aligned with leftist politics, not to mention its wide distribution of class alliance and its ambiguity in terms of how it functions as labour. When artists organize themselves in a public form of politics (to be distinguished from the behind-closed-doors form of politics by which the Art System perpetuates itself) we can see that it tends to use as models organized labour and student activism, or else builds upon its existing participation in social-justice movements as the "artistic wing." Artists generally appropriate the structure of existing political formations, based either on the firsthand knowledge of individual experience within other circles or else based on a superficial understanding of how these formations represent themselves.v

Public protest itself has operated in two distinct modes throughout the last decade: an Oriented politics which is formally constructed in traditional left/right means of manifestation (such as marching, picketing, rallies with speakers, etc.), and a Disorientated politics which is decentralized, dispersed and essentially anarchic and indeterminate.vi This Disoriented mode can range from the highly articulated, such as the rebellion in Greece during the winter of 2008 where there was an established and conveyable political worldview informing the actionsvii, to the unarticulated, such as the case of the London Riots in 2011 whose root causes were similar to the former but whose actions exceeded their own self-understanding.viii More recent movements such as Occupy and the Indignados of 15M exemplify a merging of the Oriented and Disoriented mode of protest, presenting a host of interesting tensions and possibilities. The notion of "orientation" being addressed by this distinction is simultaneously directional (as in the political horizon or specificity of its targets) and related to the subjectivity of its participants (both negating and self-actualizing).ix

The same ongoing global economic crisis which has provoked so much recent protest has compelled cultural workers to respond by a means which relate to their particular fields. European discourse has mostly focused on ideas developed by the Italian "Operaismo" ("Workerism") movements of the 60's and 70's and theorists such as Antonio Negri, Mario Tronti and many others, invoking concepts such as "post-fordism" as a description of creative, intellectual and affective labor, and "precarity" as a state of existence without predictability or security and affecting our material or psychological well-being, as a means of articulating the conditions of contemporary artists.x Meanwhile, in North America and the U.K. there has been a rekindled fascination with the identity of "Labor" and a move to define cultural production as "work", in particular since 2008 with the arrival of that year's economic crisis.xi This has led to a both tactical and potentially nostalgic trend toward over-identification with the "Worker" or "Artworker". In line with this, artists have increasingly developed activist formations primarily of an Oriented character. More or less concurrent groups such as W.A.G.E. (est. 2008), Liberate Tate (est. 2010), The Precarious Workers Brigade (est. 2010), Occupy Museums (est. 2011), Art & Labor (est. 2011) and dozens of others organize their resistance towards a combination of explicit demands and generalized reforms using boycotts, pickets, public campaigns and collective organizing with varying levels of success. They often appear to be modeled after, or inspired by, earlier organizations as diverse as the Art Worker's Coalition (1969-1971), Group Material (1979-1996), Political Art Documentation and Distribution (PAD/D, 1980-1988),The Guerilla Girls (est. 1985), and Gran Fury (1988 - 1995), all of whom similarly operated in more or less an Oriented vein.xii It is within this context that the Art Strike re-emerges as a tactic, a point of reference and an as yet unrealized potential. However, as it has evolved over a half century, the Art Strike has resisted Orientation, manifesting instead as a Disoriented refusal of the power of the market and the state, and in its generality, proving incompatible with the linear activities of contemporary activist art.

PAD/D project

The New York Art Strike

By the late 60's, the US was mired in its war against Vietnam while simultaneously experiencing enormous social upheaval within its own territory. Demonstrations against the war had become massive and generalized, civil rights struggles had become more militant and labor unions and workers everywhere were striking with increased regularity. Artists themselves had become more organized in their efforts to protest the war in Vietnam and to address systemic racism, police violence and gender inequality. In 1968, led by prominent artists and critics, the Art Workers Coalition (AWC) was formed in response to kinetic-sculptor Vassilakis Takis' theft of his own artwork from New York's Museum of Modern Art.xiii The group issued demands regarding museum reform and artists rights, culminating in a public meeting of hundreds of cultural producers in April of 1969. Collectively they understood the degree to which their artwork served multiple economies - political and social - and sought to use this as leverage against institutional power.xiv

On May 15th, 1970, Robert Morris, then already a well known sculptor and conceptualist, closed his one-man show at the Whitney Museum stating:

"This act of closing ...a cultural institution is intended to underscore the need I and others feel to shift priorities at this time from art making and viewing to unified action within the art community against the intensifying conditions of repression, war and racism in this country."xv

Unlike previous actions taken up by the AWC and their antecedents,xvi whose Oriented logic pushed specific demands upon arts institutions, this act was of a more general character. Morris viewed his initial strike as being against the art system itself and, echoing a similar withdrawal from Using Walls, a group show at the Jewish Museum earlier that year,xvii his gesture concluded that the power of the art institution, including all the members of government, finance and the art world who inhabited these spaces, was interchangeable with the violence of Vietnam as a deserving subject of attack. Though begun with explicit demands (the early closing of his show; the opening of the building as a meeting hall), Morris opened up the possibilities of an unlimited refusal of power and violence, a Disoriented position articulated by the raising political consciousness of the time which saw a whole system at work.

Morris' shuddering of his exhibition immediately inspired a city wide day of action undertaken by the AWC: "The New York Art Strike against Racism, War and Repression." On May 22nd, nearly every cultural institution in the city was shut down for one day, with Frank Stella closing his show at the MoMA and hundreds of artists picketing and rallying in front of the obstinate Metropolitan Museum of Art. It is important to note that, taking a cue from Morris, participants generally positioned the site of labor at the point of exhibition. As art historian Julia Bryant-Wilson points out, "those taking part in the strike went under the assumption that aesthetic practices were productive and that their stoppage would interrupt the functions of economic or social life in some crucial way."xviii Their strike did not confront the act of art making, but rather its intercourse with the institution itself. Yet within the inner discourse of the AWC this was contested. Some made forceful arguments for abandoning the making of any artwork that was not in the service of the revolution, while others called for a shift towards art which could appeal to and radicalize the proletarian masses, a proposal that was roundly rejected as a return to some form of Social Realism.

Perhaps the most radical form of refusal that coincided with the formation and agitation of the AWC was General Strike Piece by Lee Lozano. Already emerging as a figure of the NY art world thanks to her "polymorphously perverse" and oddly surreal figurative painting, Lozano was also an early conceptualist who kept a diary of "word pieces" that acted as instructional devices exclusively for her own behavior and actions.xix In a statement read during the AWC's meeting in April, Lozano declared herself in excess of the limits of the "artworker" identity, identifying herself as an "artdreamer" who would "participate only in a total revolution simultaneously personal and public."xx As Helen Molesworth points out, her "word pieces" inverted the artist's role of attending their gaze upon the the art object and instead "train(ed) her attention on the public and private functions of herself as an artist."xxi Beginning with Dialogue Piece, she laid a foundation for an exodus from the problem of the art as a commodity, not purely by art's "dematerialization" but by the flight of the artists themselves. With 1969's General Strike Piece, Lozano began systematically exiting the art world by refusing to attend "uptown functions" be they openings, parties at museums and galleries, screenings, concerts or any other "gatherings related to the art world," while simultaneously initiating a "boycott of women" which resulted in her leaving New York for a life of relative isolation in Dallas where she continued to refuse any interaction with either the art world or any woman in public life. Molesworth, who describes this double refusal as "consummately idealistic" and "utterly pathological" (respectively) recognizes both things being refused, capitalism and patriarchy, as "incredibly powerful parameters of identity... systems with rules and logics that are public with personal effects."xxii

Art Strike's Reprise

Elements of Lozano's remarkable refusal arise again in 1974 when German emigre Gustav Metzger published a manifesto titled Years Without Art 1977-1980 in the Institute of Contemporary Art's exhibition catalog for Art into Society - Society into Art. Metzger, sensing his own ascent within the art world, extends an invitation to his peers to withdraw in protest of art's increased commercialization and to bring about the destruction of an art system "smothered" by capitalism. In Years Without Art, Metzger critiques the practices of artists engaged in political struggle, regarding their activity as "reformist, rather than revolutionary," merely focused on "the use of their art for direct social change, and actions to change the structures of the art world," countering with an argument that the "deep surgery of the years without art will give art a new chance." Like Morris before him, Metzger views the art system's apparatus of exhibition, of publicity and of funding as totally interdependent, concluding "damage one part, and the effect is world-wide." In other words, to destroy capitalism one need only begin with art.xxiii

Metzger had already established himself as an iconoclast in the avant-garde tradition when as early as the 50's he had begun championing "Auto-Destructive Art" as a rejection of the art commodity, an acknowledgement of the self-destructive nature of society and the environmental impact of overproduction in the post-war period. It is useful to see his call for Years Without Art as an extension of his auto-destructive practice which aspired to be "an attack on capitalist values"xxiv and which paradoxically resolves itself by "re-enacting the obsession with destruction, the pummeling to which individuals and masses are subjected."xxv In refusing to make art, the artist would enact a process which could destroy the art world through a self-imposed, and potentially brutal asceticism. Yet it was also his hope that artists who heeded the call would engage in an active understanding of the political realities in and outside of the art world.

In a sense Metzger was inviting a situation (not wholly unrealized) where the artist would engage theory and research in an expanded field before returning to the manipulation of materials into art objects. In Years Without Art he seems sympathetic to the difficulties of refusing art as a productive act, but imagines a subjective transformation similar to what Molesworth says of Lozano's refusal to speak to women. Both can be framed as choices which "render life a constant struggle" in order for the artist to become more "attuned to the problematics, limitations, and systemized nature of patriarchy (and capitalism)... to disallow the status quo to be perceived as natural, to heighten our awareness, to focus our attention on the problems of patriarchy (and capitalism)."xxvi These choices interrogate the very privilege which makes them a choice in the first place, a choice that most artists refused, no matter how ethically demanding. Metzger was the only artist to heed his own call. He stopped producing art for the three years of his strike and then entered into self-exile from his home in England, only returning to a visual art practice much later.

In 1979, already two years into Metzger's solitary refusal, the Yugoslavian based artist Goran Djordjevi?? made a call for further discussions on the possibility of an International Strike of Artists, sending letters of invitation to artists, curators and critics, asking if they would "take part in an international strike of artists... as a protest against art system's unbroken repression of the artist and the alienation from the results of his practice." He argued the importance of "(demonstrating) a possibility of coordinating activity independent from art institutions" implying a dual and equal significance of refusal and autonomous organization. In response he received over 40 letters, including replies from former Art Workers Coalition members Carl Andre, Lucy Lippard and Hans Haacke, all of whom respectfully declined.xxvii Djordjevi?? himself did not enter into a total withdrawal from the art world at the register of Metzger or Lozano, but instead immediately began what would become his primary project of attacking the concepts of authorship and originality. His work, which includes faithful reproductions of high modernist paintings by Mondrian and Malevich, as well as entire exhibitions in miniature, aims to destroy not merely the material foundations of the art system but the ontological and epistemological conditions which make it possible. His work argues that the "fake" acts as an infection which undermines the ability for originals to claim legitimacy. Djordjevi?? believes that the means by which art has been constituted and the art system reproduces itself is utterly tied to the fantasy of originality and the myth of the unique and auratic art object.xxviii

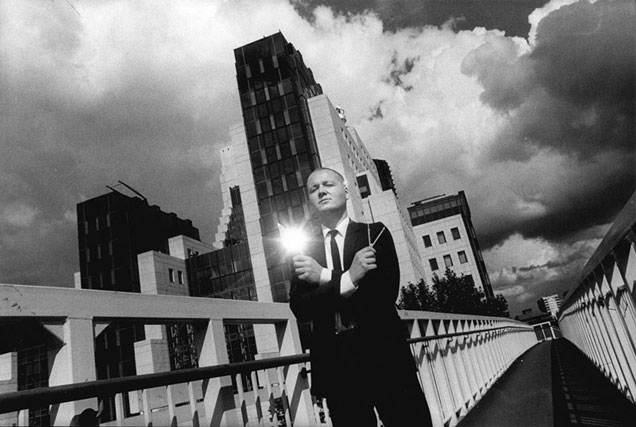

Gustav Metzger

The Readymade Art Strike

Djordjevi?? proposes acts of subversion through plagiarism and montage which are similar to those performed by the early 20th Century artistic avant-garde, who likewise sought to expose an art system that artificially produced capital from objects which were devoid of any proper use value. This phenomena was resolutely established by Marcel Duchamp with the introduction of his readymades - the display, controversy and acceptance of Fountain revealing the blatant arbitrariness of all the same categories that Djordjevi?? still contests. Perhaps not coincidentally, Duchamp himself enacted a form of strike later in his career, convincing the world that he had given up art for the last 25 years of his life, preferring to play chess. Even if his total withdrawal of labor resembled a strike, he did not claim any sort of explicit critiquexxix, nor was his gesture seen as a refusal of his increasing stature as an artist, and though it is often discussed with fascination, his abandonment of the art world was a myth. He had continued to develop a major work during his supposed retirement - Etant Donnes - and made arrangements for its installation to occur after his death.xxx

Duchamp was a part of an avant-garde milieu that established as an aspiration the end of a separation between art and life and made constant rhetorical battle with the bourgeois culture that in its time held total institutional sway over the fine arts. It did so because it imagined itself to be creating the conditions for a social rupture through its own ruptures within art. In this way, they attempted to perform a sympathetic magic, as if by breaking with convention within the frame of painting, sculpture, dance, theater, music or cinema, they would be setting off a chain of events that would reshape the whole world. Renato Poggioli identifies within this political mysticism a tendency in the avant-garde towards self-sacrifice for the future - an agonistic futurism where the artists of the avant-garde act as "precursors" to the inevitable artistic horizon that they can foresee but not attend. This "self-immolation for the future artist" as he puts it, forms a dialectical bond to the deeply antagonistic nihilism of their attack on society and its sensibilities.xxxi The very notion of a strike against art would be impossible without this frame of belief.

This tendency which we are tracing emerges in more or less explicit terms throughout the last hundred years, not simply prior to the second world war but continuously into the anti-art practices of the present day. Exemplary of the post-war manifestation of the avant-garde is the Situationist International (SI) who in principle advocated that art should be surpassed in order to be realized in life. Primarily concerned with literature, they nonetheless viewed Dada and Surrealism as their parentagexxxii and were clearly concerned enough with art to totally disavow it as a practice and "break" with those members of their group who continued to engage with it. "The paradox of this position" surmises art historian Claire Bishop, "is that the SI rejected art but continually invoked it as the benchmark of non-alienated life."xxxiii Instead of traditional art-making they called for the construction of "Situations," actions which were immediate, instantaneous ruptures, self-determined and impossible to commodify.xxxiv This desire for what Henri Lefebvre called "the vital productivity of everydayness"xxxv is combined by the SI with a brutal asceticism - the refusal to make artwork until such time as the world is transformed - which continues to be the irreducible feature of the Art Strike in nearly all its forms.

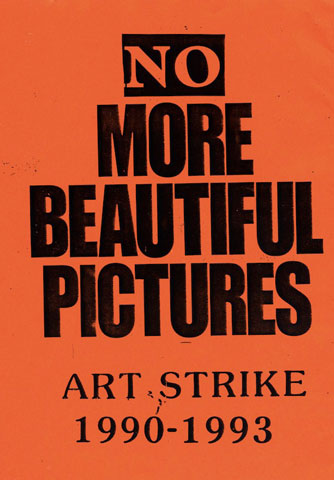

The SI's principals of détournement as a radical appropriation of existing media and their theoretical assault on art would be transferred to another generation of neo-avant-gardists who would claim The Art Strike itself as a type of readymade. The Art Strike 1990-1993 was initiated in 1985 by Praxis, a group primarily composed of one individual, British artist, writer and provocateur Stewart Home.xxxvi Home had been involved in Fluxus, Mail Art and Neoist networks where he championed various avant-garde practices primarily borrowed from Dada and the Situationists. He advocated for plagiarism (for essentially the same reasons that Djordjevi?? championed the copy)xxxvii and was a proponent of the "multiple use" or "open name" which invited participants to publish, perform and create under a shared moniker (such as Monty Cantsin, Karen Elliot, Luther Blissett and the magazine SMILE).xxxviii Home's views of the Art Strike were self-reflexively insincere, presuming not that a general strike would occur but that the organizing around the Art Strike might "create at least as many problems as it resolved."xxxix

Stewart Home

"The importance of the Art Strike lies not in its feasibility but the possibilities it opens up for intensifying the class war. The Art Strike addresses a series of issues; most importantly among these is the fact that the socially imposed hierarchy of the arts can be actively and aggressively challenged."xl

Home did in fact go on strike between 1990 and 1993, but in spite of the impressively large numbers of participants in the movement leading up to the event, only a very few artists seem to have committed to this withdrawal.xli Ironically, the years preceding the Art Strike were massively productive as dozens of artists networked through correspondence and other collective activities producing periodicals, recordings, propaganda and various convergences as part of the campaign. Having established the Art Strike as a de-authored readymade, it has since reappeared in exhibitions and publications and continues to be a major reference point for contemporary avant-gardist activity.xlii

SPART Action Group, Alytus Art Strike Biennial

As just one example, artists in Alytus, Lithuania held the Art Strike Biennial in 2009 as a direct response to Vilius being named the European Union City of Culture for that year. The effects of events such as the City of Culture and international biennials such as Manifesta, especially in smaller and less economically developed cities, are similar to other neo-liberal mega-events such as the Olympics.xliii Radical transformations of the urban space occur in highly undemocratic ways, accompanied by a shifting of public wealth into private hands, and often the exclusion of the very artists who make up the local artistic community. As an act of resistance, the Art Strike Biennial proposed to exhibit no artwork, nor provide any spectacular proof of art occurring.xliv Instead, a long series of seemingly disconnected performances, disruptions, protests and public conversations occurred involving an array of contemporary surrealists, neo-dadaists, situationists and other artists with shared sympathies.xlv

Art Strike as Human Strike

I have attempted to trace through the conceptual and literal withdrawal of Robert Morris, the radical flight of Lee Lozano, the auto-destruction of Gustav Metzger, the disappearance of authorial authenticity in Goran Djordjevi??, and the attack on the very category of art and the artist by Stewart Home, a shifting phenomena that can be seen as a performance, a conceptual artwork, a political strategy and a general tendency that is present to greater or lesser degree in all avant-gardist work. Over the last four decades, the Art Strike has become totally dislodged from any hierarchically organized, Oriented political formation, and in doing so it has abandoned the authentic gesture of earlier examples. It is unrecognizable when compared to the very first self-declared Artist Strike in the US during 1937 which agitated against the dismantling of the Works Progress Administration, a government program that hired and paid unionized artists living wages. The militancy of those sit down strikes which occupied buildings and held administrators hostage exceeds anything that has been staged since in the name of the Art Strike, its legacy more visible in recent student occupations in Vienna, Zagreb, California and elsewhere.xlvi Also gone is the trans-disciplinary solidarity of visual artists, musicians, dancers and theater actors who combined in the late 1930's into a form of general strike, stark in contrast to the isolation of the interdisciplinary contemporary artists who have championed the tactic ever since.

As of today the Art Strike is a decentralized catchall for neo-avant-gardist activity, inclusive of interventions, demonstrations and refusals of both a public and private nature. Its enemies are both the art commodity and the concept of art as a category which require and sustain the current economic and political order. This "readymade-ness" of the Art Strike, as exemplified in Art Strike 1990-1993, finds itself reflected in the concept of the "readymade artist" as developed by Claire Fontaine. As they explain it, the "self-reproducing fabric called the art world" has produced a set of strict norms which affect not art objects so much as "the domain of the production of artists."xlvii Claire Fontaine echos the critical relocation of the crisis in art from the institution to the artist themselves, both theoretically and demonstrably through plagiaristic acts similar to those of Djordevic, Stewart Home and his contemporaries,xlviii proposing that the terrain of conflict between art and society can be productively explored through the embrace of the artist as a readymade figure.

The Art Strike Biennial extends that critique to the museum and the biennial, even to the city itself. Responding to Djordevic, Marina Gržinic suggests that the recuperation of Duchamp's work by the art market is proof that "the content of a readymade is not the concrete object, but its context - i.e., the art gallery or museum... and therefore, the object of the readymade is the gallery system in itself."xlix In this way even it's critique is a readymade, it's language, gestures and irresolution as much a prefabricated situation as the biennial culture it is attempting to refuse. It is here where the Art Strike as a form of "institutional critique" inhabits Andrea Fraser's diagnosis of the tactic's inevitable recuperation, "the insistence of institutional critique on the inescapability of institutional determination," a recognition that the heritage of the avant-garde is not the eradication of the institution of art but of its limits. To Strike against the institution is to strike against ourselves "because the institution of art is internalized, embodied, and performed by individuals, these are the questions that institutional critique demands we ask, above all, of ourselves."l

Art Strike 1990-1993

Yet what if this de-authored rejection is a tactic for something other than critique or reform? If the gesture is itself hallowed of its revolutionary potentials in as much as it embraces and flaunts its marginality and counter-cultural position, perhaps we can find another purpose to its continual renewal. What activities such as the Art Strike 1990-1993 and the Art Strike Biennial propose - in productive terms - is a communizing of artists in an act of living against a culture of violence, oppression and environmental devastation. While this may not address the explicit demands made by the Art Worker's Coalition, Gustav Metzger, or even Goran Djordevic, to the artistic share holders of the mainstream art market, it does open a space of exodus where artists, curators and critics may depart if they choose. It creates networks of relationship, alternative and autonomous sites of activity, and perhaps most controversially it proposes models for praxis which might unite aesthetics and post-politics outside of the constraints of authoritarian judgement, criticism and forms of value.li It is a politically Disoriented art which positively negates authorship, property ownership and social hierarchies. It is the withholding of labor in service of the radical play and autonomous self-actualization which was promised a century ago by the artistic avant-garde.lii

If this does offer some promise, it holds within itself a contradiction: its very impacts seem to depend upon the art system it attempts to enact an exodus from, as invariably it circles back, if not to the institutions of art, then the chronology and values of Art History. It must resist submission to what Djordjevi?? refers to as "the story of Art History", but because the forms of resistance it relies upon are most often constituted by its conditions, it invariably reaffirms and perpetuates this dominant narrative.liii It defines itself in opposition to its enemy and thus validates and legitimates that enemy using a set of terms not of their own making. In light of this, the logic of flight as employed by Lozano remains the last refuge of refusal that can resist reform or recuperation. This exodus, alluded to by others from Duchamp to Richard Long but rarely enacted with such courage and conviction, exemplifies the concept of "Human Strike" which might yet be the last remaining potentiality for an effective Art Strike. As defined by Claire Fontaine, "this type of strike... is the most general of general strikes and its goal is the transformation of the informal social relations on which domination is founded."liv It is a refusal not only of structures of power but the internalized self-discipline which perpetuates these structures. It is a strike against oneself; "it kills the bourgeois in all of us, liberating unknown forces."lv Again we return to Paggioli's conception of the avant-garde and its self-annihilating character. He terms this sacrifice as "futurism" - a generalized ontology of the avant-garde which views itself as the means by which the emancipated horizon of art is reached.lvi Human strike rejects this futurism, claiming itself to be (in the terms of Walter Benjaminlvii) "a pure means, a way to create an immediate present here where there is nothing but waiting..." Claire Fontaine continue:

"The reflex of refusing any present that doesn't come with the guarantee of a reassuring future is the very mechanism of the slavery we are caught in and that we must break. To produce the present is not to produce the future."lviii

Here is a foundation for an Art Strike which acts as an attack upon the art system not exclusively by the withholding of laborlix but primarily by means of an attack on the subjectivity of the artist themselves. An Art Strike that takes the form of a human strike is a much more deeply Disoriented political gesture which makes a claim that for the art system (as an extension of capitalism and all other oppressive systems) to be transformed through destruction, the artist must disappear with it.

What then appears in the void? This is the the question, the existential anxiety, which seems to inevitably turn the insurrectionary artist away from their own immolation and back towards the institution. It would seem that the art system remains the only source of a narrative which can articulate the aspirations of the Art Strike, even while nullifying its most radical possibilities. It is for this reason that the Art Strike must embrace a prefigurative gesture which can produce a real difference worth inhabiting. To some extent we already see this in a multitude of vernacular practices that live on the margins and in the blind spots of contemporary art, from the private culture of domestic arts and craft to the ephemeral practices of street art or the cultural products of communities who actively resist visuality, documentation and surveillance. We should remember that human strike is not merely a refusal but a form of life that refuses; Art, as a way of living, should already and always be a form of human strike. As a practice, Claire Fontaine's art-making is utterly compatible with the existent art world, which can be read as either a concession to that world's ubiquity or else testifying to a belief that Art as we know it is still a ground worth fighting for, not only against. Writing as Walter Benjamin, Djordjevi?? argues that it is the "story of Art History" which must be challenged. In this regard we can see the self-identified surrealists, dadaists, situationists, feminists, stuckists, queers and a multitude of other marginal art-historical-non-conformists as an embodiment of a counter-history that, were it infectious enough, might meaningfully disrupt the dominance of our existing system. Perhaps already successful in some regard is the emerging historicization of Social Practices which is tracing a lineage of participatory artwork across the narrative of modern art which had heretofore given primacy to the material art object.

Yet none of these projects are dislodged from the actually existing art-world any more than actually existing capitalism, which is to say that they remain implicated and interconnected with the same practices and the same stories they wish to reject. When Djordevic invites us to imagine a new story of Art History as a means of flight, he might as well be inviting us to imagine a human system other than capitalism. This is in fact what a successful Art Strike requires, and why a mere reform of the existing art system, in spite of the real material good it may do in the present, will inevitably fail to meaningfully alter our power relations. This is the impossibility of the Art Strike. Yet our aspirations are not remote, only just beyond our present moment, ever imminent, waiting to be imagined, spoken, enacted and embodied.

Claire Fontaine

Footnotes

iHere and throughout I am using Renato Poggioli's tracing of the emergence of the Avant-garde as a theory into the world of Art, in particular it's transformations from use in radical left politics to an equivalence with various modernist practices in art. Renato Poggioli, The Theory of the Avant-garde, trans. by Gerald Fitzgerald. (Cambridge, MA/London: Harvard University Press, 1968).

iiPeter Burger, Theory of the Avant-garde (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1984). This tension is explored in great detail in Gavin Grindon, "Surrealism, Dada, and the Refusal of Work: Autonomy, Activism, and Social Participation in the Radical Avant-Garde," Oxford Art Journal 34.1 (2011): 79-96. In particular he attempts to move beyond the limited criteria of judgement for the "failure" of the avant-garde as applied by Burger and others by looking at its refusal of "work" and social organization.

iiiThis is my own definition though it is only inconsistent with common definitions in as much as it is left open to concepts of strike which do not privilege traditional conceptions of labor such as the "human strike" as articulated by Claire Fontaine (see note 54 below).

ivArnold Roller [Siegfried Nacht], trans. Max Baginski, The Social General Strike (n.p., 1905)

vNumerous examples appear in recent alter-globalization movements and the international Occupy movement. What has been termed Tactical Media offers both an easy illustration of this and several complications as well. See Brian Holmes, Unleashing the Collective Phantoms:Essays in Reverse Imagineering (New York: Autonomedia, 2008); Gregory Sholette and Nato Thompson, eds., The Interventionists: User's Manual for the Disruption of Everyday Life. (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2004) and Nato Thompson, ed. Living As Form. (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2012).

viI am not only interested in addressing contemporary politics in a way that circumvents established binaries of Left and Right, but as well I am trying to reconcile the emergence of tendencies which are often infused with both communism and anarchism in character but refuse these affiliations and are not determinedly Leftist as might be assumed. Nor are they centrist though they have a popular character that supports a broad intersection of political identities to be activated within them.

viiA.G. Schwarz, Tasos Sagris & Void Network, eds., We Are An Image From The Future: The Greek Revolt of 2008 (Edinburg/Oakland: AK Press, 2010)

viiiBoth the riots in London and those in Greece were sparked by the police murder of a local youth and fueled by the daily violence of poverty, police repression and the deadening social space of capitalist society. The political and emotional justifications for the former are detailed in The Guardian's Reading the Riots: available from http://www.guardian.co.uk/uk/series/reading-the-riots; accessed 11-22-2012.

ixIt is important to note that I am appropriating very intentionally from Sara Ahmeds' use of "disorientation" when discussing Queer identity and the act of queering itself in Sara Ahmed, Queer Phenomnology: Orientations, Objects, Others (Durham: Duke University Press, 2006). In particular I am fascinated with where Ahmed's description of the process of queering becomes complicated with political contradictions: "It is not that disorientation is always radical. Bodies that experience disorientation can be defensive... so, too, the politics that proceed from disorientation can be conservative, depending on the 'aims' of their gestures, depending on how they seek to (re)ground themselves." (158) This complication of politics, along with the use of "ground" as a literal analogy for subjectivity begins to overlap with similar conceptions of "unsettling" in relation to Decolonization as well as the "post-foundational politics" detailed by Oliver Marchart. Another influence on this thinking is A.K. Thompson's use of the theories of Frantz Fanon, Judith Butler and others to consider riots, the "black bloc" tactic and their role in the formation of "post-representational political subjectivities"; see A.K. Thompson, Black Bloc, White Riot: Anti-Globalization and the Genealogy of Dissent (Edinburg/Oakland: AK Press, 2011).

xThere are numerous arts related publications which offer telling examples, including Arts In Society: Being and Artist in Post-Fordist Times, Pascal Gielen and Paul De Bruyne, eds. (Rotterdam: NAi Publishers, 2009); No Order: Art in a Post-Fordist Society no.1, Marco Scotini, ed. (Berlin: Archive Books, 2010); Are You Working Too Much?: Post-fordism, Precarity, and The Labor of Art, Julieta Aranda, Brian Kuan Wood, and Anton Vidokle, eds. (Berlin: e-flux, 2011)

xiSee as a an example of the North American response, Temporary Services, eds. Art/Work: A National Conversation About Art, Labor and Economics (Chicago: Half Letter Press, 2009).

xiiArguably Group Material would be the exception as their work was less overtly a traditional form of protest. In fact their work functioned most often as an intervention into the art-world by using the framework of exhibition making to generate new sites for the discussion of politics.

xiiiJulia Bryant-Wilson, Artworkers: Radical Artistic Practice in the Sixties (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2010), 13. Additional references for the AWC and the NY Art Strike include Julie Ault, ed., Alternative Art, New York, 1965-1985 (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2002); and Alan W. Moore "Artists Collectives: Focus on New York 1975-2000," in Collectivism after Modernism:The Art of Social Imagination after 1945, ed. Blake Stimson and Greg Scholette, (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2007)

xivThey shared members with other groups including the Black Emergency Cultural Coalition (which preceded the AWC; 1968), the Guerilla Arts Action Group (1969-1976), the Emergency Cultural Government (organized against participation in the U.S. pavilion at the Venice Biennale; 1970) and Women Artists in Revolution (1969-1971). These groups themselves were prefigured or else emerged alongside more anarchic artist/activist projects including Black Mask (1966-1968), Up Against the Wall Motherfucker! (1968-1971) and the Yippies (est. 1967), all of whom had been influenced by the anarchist theater of San Francisco's Diggers (1966-68), not to mention the general cultural and political influence of the New Left and the social and political organization of feminists, gays and people of color.

xvBryant-Wilson, 113.

xviSuch as the New Deal era's artists' unions mentioned above who initiated a succession of militant sit-ins between 1936 and 1937 in an attempt to salvage the barely adequate economic support provided by the US government's Works Progress Administration and the Federal Artist Project which was to be gutted following Roosevelt's re-election. See Richard D. McKinzie. The New Deal For Artists (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1973), 93-102

xviiMorris was accompanied by his fellow exhibitors in Using Walls: Richard Artschwager, Mel Bochner, Daniel Buren, Craig Kauffman, Sol LeWitt and Lawrence Weiner. Bryant-Wilson, 246n101

xviiiIbid, 117. This is also the original logic behind "Day Without Art", an annual commemoration of artists who have died as a result of AIDS and those who survive. As a form of Art Strike, it is interesting to consider that it has embraced a productive mode over time, promoting the presentation of work corresponding to the theme, rather than the withholding of work as a means of enacting social and political change.

xixHelen Molesworth, "Tune in, Turn on, Drop out: The Rejection of Lee Lozano," in Art Journal vol. 61, No. 4 (Winter, 2002), 64-71

xxLee Lozano, "Open Hearing," Art Worker's Coalition Handbook (New York: 1969), 38.

xxiMolesworth, 70.

xxiiIbid.

xxiiiGustav Metzger, "Years without Art 1977-1980," in Gustav Metzger: History History, ed. Sabine Breitwieser (Vienna: Generali Foundation, 2005), 262-263.

xxivGustav Metzger, " Auto-Destructive Art, Machine Art, Auto-Creative Art", in Ibid., 228.

xxvGustav Metzger, "Manifesto Auto-Destructive Art", in Ibid., 227.

xxviMolesworth, 71.

xxviiThese former participants in the NY Art Strike generally responded by arguing that they had more effect working within the art system and that they would be punishing no one but themselves by refusing to make work. Carl Andre's response is exemplary: "From whom would artists be withholding their art if they did go on strike? Alas, no one but themselves." (as quoted in Bryant-Wilson, 217). A collection of responses were reprinted in James Mannox, ed., The Art Strike Papers (Edinburg: AK Press, 1991) and are available online from The Stewart Home Society: http://stewarthomesociety.org/features/artstrik26.htm; accessed, 11-25-2012.

xxviiiThere is little scholarship on Djordjevi?? in english, but he has been written about in the context of NSK and the retro-avant-garde by Marina Gržinic. See Marina Gržinic, "Neue Slowenische Kunst" in Impossible Histories: Historical Avant-gardes, Neo-avant-gardes, and Post-avant-gardes in Yugoslavia 1918-1991, ed. Dubravka Djuric, Miško Šuvakovic (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2003), 246-269 passim. Djordjevi?? is also known for staging lectures authored and performed by "Walter Benjamin." Of particular relevance to the above essay would be his text, "Unmaking Art" from Walter Benjamin, Recent Writings (Los Angeles/Vancouver: New Documents, 2013).

xxixWhen asked why he "retired" from the world of art, Duchamp replies "I never had any why... there was no vow, no intention..."; see unattributed interview: available at http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uzHXus7dQlw; accessed, 11-22-2012.

xxxMarcel Duchamp, Marcel Duchamp: Manual of Instructions: Etant donnes, revised edition (Philadelphia: Philadelphia Museum of Art, 2007)

xxxiPoggioli, 60-74

xxxiiClaire Bishop, Artifical Hells: Participatory Art and the Politics of Spectatorship (London/New York: Verso, 2012), 81

xxxiiiIbid., 102.

xxxivIbid., 86

xxxvCited in Ibid., 86. See also Ibid., 306n39

xxxviStewart Home, Neoism, Plagiarism & Praxis (Edinburg: AK Press, 1994), 26.

xxxviiIbid., 49-51

xxxviiiIbid., 6, 11 and 52. For a contextual history of this tactic as it relates to the Luther Blissett Project, see Marco Deseriis' essay, "Lots of Money Because I am Many: The Luther Blissett Project and the Multiple-Use Name Strategy" in Begüm Özden Firat and Kuryel, Aylin, Cultural Activism: Practices, Dilemmas, and Possibilities (Editions Rodopi, 2011). The radically transformative potential of escaping from the limitations of authorship and visibility are interestingly articulated by Sthephen Wright in his text, Users and Usership of Art..."Envisaging an art without artwork, without authorship and without spectatorship has an immediate consequence: art ceases to be visible as such. For practices whose self-understanding stems from the visual arts tradition – not to mention for the normative institutions governing it – the problem cannot just be overlooked: if it is not visible, art eludes all control, prescription and regulation..." Stephen Wright, Users and Usership of Art: Challenging Expert Culture (transform, 2007): available at http://transform.eipcp.net/correspondence/1180961069#redir#redir; last accessed, 11-25-2012.

xxxixHome, 26.

xlIbid.

xliAccording to James Mannox, Home was joined only by Tony Lowes and John Brendt. See Mannox, The Art Strike Papers.

xliiFor example, Justin Hoffman has exhibited ephemera from the Art Strike along with original materials in 1996 as part of the exhibition Art is Not Enough at the Stendhalle, Zurich. See Justin Hoffman, "The Idea of the Art Strike and its Astonishing Effects" in Gustav Metzger: Retrospectives, ed. Ian Cole (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999).

xliiiBik Van der Pol, Alissa Firth-Eagland & Urban Subjects, eds., Momentarily: Learning from Mega-Events (Vancouver: Western Front, 2011).

xlivAlytus Biennial: available at http://www.3.alytusbiennial.com/; last accessed, 11-25-2012.

xlvActivities of the Art Strike Biennial included a series of processions called Monstrations with music, performances, signage completely written in Spanish and "Picket Line Fashion" made in collaboration with a local tailor; a Three Sided Football match (a variation of traditional football with the addition of a third competing team, first invented by the London Psychogeographical Association c 1993); and a fair amount of drinking and socializing with bar room lectures by Franco Berardi Bifo and other visitors. These were among other activities transpiring in various sites that were not wholly dissimilar from ubiquitous forms of Social Practices, a category of art-making which has itself been folded into the larger umbrella of the Neo-avant-garde.

xlviSee note 11 above; Regarding the various university occupations see Unibrennt: http://unibrennt.at/; last accessed, 11-25-2012; The Occupation Cookbook or the Model of the Occupation of the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences in Zagreb, trans. Drago Markisa (London & New York: Minor Compositions, 2011) ; After the Fall, (Oakland: Ardent Press, 2010).

xlviiClaire Fontaine, Readymade Artist and Human Strike: A Few Clarifications (n.p., 2005).

xlviii"Claire Fontaine" itself is a name appropriated from a common french notebook, an action that is one means of presenting the group as a "readymade artist". This conception is akin to the 'open' and 'multiple' name practices of Home and others. Clair Fontaine's critique of the self-disciplining quality of artistic work as manifested in the "readymade artist" also appears to be an echo of Home who wrote: "Other issues with which the Art Strike is concerned include that series of 'problems' centered on the question of 'identity'. By focusing attention on the identity of the artist and the social and administrative practices that an individual must pass through before such an identity becomes generally recognized, the organizers of the Art Strike intend to demonstrate that within this society there is a general drift away from the pleasures of play and simulation; a drift which leads, via codification; on into the prison of the 'real'." See Home, 26.

xlixMarina Gržinic, Situated Contemporary Art Practices: Art, Theory and Activism from (the East of) Europe, (Ljubljana: ZRC Publishing, 2004), 113.

l Andrea Fraser, "From the Critique of Institutions to an Institution of Critique," Artforum, September 2005, 278-286.

liSee Gregory Sholette, Dark Matter: Art and Politics in the Age of Enterprise Culture (London: Pluto Press, 2011). Sholette suggests that the "glut" or "over-supply of artistic labor," produced in part by the authoritarian use of aesthetic judgement, materially benefits the art market in a way that is increasingly visible in the form of income inequality. This prompts him to ask "What possible consequence would result from a mutiny within the global art factory?" (116). While Sholette doesn't foresee a general strike by artists in the form of a massive abdication, he does posit it as a real possibility which could render the current art world inoperable.

liiGrindon, 79-96.

liiiSee Benjamin, 144-146.

livClaire Fontaine, Readymade Artist and Human Strike.

lvClaire Fontaine, Human Strike has Already Begun, (n.p., 2009).

lviPoggioli, 70-71.

lviiSee "Critique of Violence" in Walter Benjamin, Reflections: Essays, Aphorisms, Autobiographical Writings, trans Peter Demetz (New York: Schocken Books,1978).

lviiiClaire Fontaine, Human Strike has Already Begun

lix"Human strike can be a revolt within a revolt, an unarticulated refusal, an excess of work or the total refusal of any labour, depending on the situation." Ibid.