Issues- Art Projects- Critical Conversations- Lectures- Journal Press- Contact- Home-

Zach Blas, Facial Weaponization Suite: Mask - May 31, 2013, San Diego, CA.

#9

bios

buy

- Zach Blas

On June 7, 2013, the National Security Agency’s surveillance program was made public in news media with the aid of whistleblower Edward Snowden, journalist Glenn Greenwald, and filmmaker Laura Portrais. Their reports revealed a suite of software designed for global, invasive data searches and analysis, including PRISM, a data-mining application used to collect billions of metadata records from various telecommunications and social media companies, and Boundless Informant, a visualization tool developed to track and analyze collected data; a third was announced on July 31, 2013, as XKeyscore, a search system that mines extensive online databases containing browsing histories and emails. Just as philosopher Michel Foucault once described the panopticon as the exemplary diagram of surveillance in the modern age, this assemblage of software, whose reach is yet to be fully known, will arguably become our contemporary replacement.

PRISM logo, 2013.

Both the panopticon and NSA software control through an optical logic of making visible. While the panopticon employs the threat of continuous visibility as a disciplinary means to achieve docile conditioning, the NSA implements technical platforms to produce informatic visibilities on populations, which is the aggregation of data for identifying, categorizing, and tracking. Here, visibility is light as information. For instance, take PRISM: a prism mediates and manages light, and as a transparent device, it suggests a mediation that is invisible, elided, obscured. Through a seemingly phantasmagorical process, a prism catches light from the world and refracts and parses it, and PRISM’s logo depicts this, as light rays are intersected by a prism to exude a single rainbow with demarcated color fields. Thus, a prism needs light to be functional, and the light that PRISM necessitates is information stored and in circulation throughout global, digital networks, severs, and databases. Such light is a particular, material form, based on standards that have been predetermined by a multifarious conglomerate of corporate, military, and state interests.

To harness this light, digital, networked surveillance relies upon the production of global technical standards, or protocols, to account for human life, what media theorists Alexander R. Galloway and Eugene Thacker label the “universal standards of identification.”(1) Technologies of identification like biometrics, GPS, and data-mining algorithms require normalizing techniques for indexing human activity and identity, which then operate as common templates for regulation, management, and governance. It is through the utilization of such standards that surveillance is able to rapidly increase at a global scale. As a result, information theorist Philip Agre claims contemporary surveillance must be more aptly termed “capture,” a computational process that signals to the often automated collection of information that is analyzed against pre-established models.(2) The construction of these models--or “grammars of action,” as Agre describes them--are designed by humans, and therefore, contain sociopolitical tendencies and preferences within their very technical architectures. Informatic standardizations, in turn, produce a conception of the human as that which is fully measurable, quantifiable, and knowable--that is, informatically visible--an enterprise that undoubtedly accelerates a neoliberal agenda where private security companies get rich by vehemently surveilling the world population. Our surveillance state now finds itself preoccupied with big data, interactive biometric marketing, and the domestication of tracking and measuring technologies, exemplified in the Quantified Self movement.

Capture technologies and their global standards of identification insidiously return us to the ableist, classist, homophobic, racist, sexist, and transphobic scientific endeavors of the 19th century, like anthropometry, physiognomy, and eugenics, albeit with the speed and ubiquity of 21st century digital technologies. The reliance of identification standardization in capture works to eliminate alterity, in which alterity becomes what remains outside computational possibilities of calculation and categorization. Of course, the grammars, or standards, of capture are technical forms of societal normalization, which amount to gross reductions in identification, where identity is reduced to disembodied aggregates of data. Thus, it is minoritarian persons that are rendered uncomputable because their difference, or alterity, cannot be digitally measured. With biometrics, for example, dark skin is commonly undetectable while other non-normative displays of age, race, or gender are frequently mis-recognized. It is those that exist as such anomalies that are informatically invisible, not emitting light, a precarious position to be sure, under threat of political violence. But, not emitting light and becoming informatically opaque is also a tactical practice of evasion, resistance, and autonomy that struggles towards social change.

Today, if control and policing dominantly operate through making bodies informatically visible, then informatic opacity becomes a prized means of resistance against the state and its identity politics. Such opaque actions approach capture technologies as one instantiation of the vast uses of representation and visibility to control and oppress, and therefore, refuse the false promises of equality, rights, and inclusion offered by state representation and, alternately create radical exits that open pathways to self-determination and autonomy. In fact, a pervasive desire to flee visibility is casting a shadow across political, intellectual, and artistic spheres; acts of escape and opacity are everywhere today! For instance, global masked protest--from Anonymous and black blocs to Pussy Riot and the Zapatistas--is a carnivalesque refusal of capture and recognition, an aesthetic tool for collective transformation beyond the perceptual registers of informatic and state visibility. Furthermore, the cypherpunk has also grown in popularity, as projects like TOR and HTTPS Everywhere develop encryption technologies that offer online anonymity.

Opaque practices expand upon critical theories like the whatever singularity, imperceptibility, illegibility, nonexistence, disappearance, and exodus. Yet, it is perhaps queer theory that has most decidedly taken an opaque turn in recent years: concepts like José Esteban Muñoz’s queerness as escape, Jack Halberstam’s queer darkness, and Nicholas de Villiers’ queer opacity understand queerness as both a refusal and utopic re-imagining of normalizing drives to recognize, categorize, and visualize, while they continue to engage the power dynamics of class, gender, race, and sexuality and their impact on the categories of visible and invisible.(3) Informatic opacity might best be understood as a mutated queerness, brought to a global, technical scale, that strives to subvert identification standardization. Ultimately, it is the late Martinique thinker Édouard Glissant’s aesthetico-ethical philosophy of opacity that is paradigmatic: his claim that “a person has the right to be opaque” does not concern legislative rights but is rather an ontological position that lets exist as such that which is immeasurable, nonidentifiable, and unintelligible in things.(4) Glissant’s opacity is an ethical mandate to maintain obscurity, to not impose rubrics of categorization and measurement, which always enact a politics of reduction and exclusion. While opacity in Glissant’s writings is not tactical, an opaque tactics, now more than ever, must be wielded to insist on opacity as a crucial ethics--because capture annihilates opacity.

Between the antimonies of identification standardization and opacity, a paradox emerges: as capture technologies are intimately bound to the privileges of citizenship, mobility, and rights, those who are either computationally illegible or unaccounted for are excessively vulnerable to violence, discrimination, and criminalization because, unlike the normatively monitored and identified, they are always risks, in that their opacity is not fully controllable. As I stated previously, it is often non-normative, minoritarian persons that are forced to occupy such precarious positions; just consider the struggles of transgender and undocumented persons with identification regulation. Thus, a paradox of recognition presents itself: political precarity is a result of informatic opacity, but utopian desires persist nonetheless in escaping the control of visibility and recognition, a battle that is seemingly more and more impossible.

The implausible proposition of becoming informatically opaque does appear insurmountable. Indeed, it is the subject of theorist Irving Goh’s essay “Prolegomenon to a Right to Disappear,” in which he turns to artistic practice for how one might proceed.(5) Similarly, in their hacktivist prophecy against capture, Galloway and Thacker claim that “future avant-garde practices will be those of nonexistence.”(6) Here, opacity is an aesthetico-political practice that enables revolt and envisions alternatives through speculative proposition and practical experimentation.

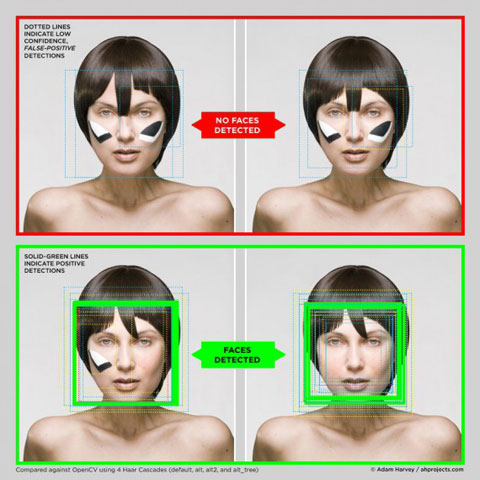

A burgeoning group of contemporary artists have commenced such an opaque practice, producing variations on how to become informatically opaque. In support of Wikileaks, Dutch design and research group Metahaven fabricated a series of scarves to evoke the organization’s dual engagement with opacity and transparency, as tactics of anonymity and encryption are used to protect whistleblowers in order to make corruption transparent. Like the protest mask, the scarf is an aesthetic accessory that blocks capture but also generates visibilities opaque to control. Also working in fashion, artist Adam Harvey develops DIY “looks” for evading face detection; in CV Dazzle, he uses make-up and hair styling to construct eccentric designs that make faces unrecognizable to computer vision systems. In workshops, Harvey teaches publics how to use cosmetics and clothing to evade various detection systems. Similarly, feminist artist Jemima Wyman, whose practice broadly explores fashion and camouflage in protest, recently organized a sew-in and fundraiser to make masks in solidarity with Pussy Riot.

Metahaven, Wikileaks Scarf, 2012.

Adam Harvey, CV Dazzle, 2011.

Jemima Wyman, Sew-In Fundraiser, 2013.

In my own artistic practice, I lead an on-going series of mask workshops and actions called Facial Weaponization Suite, in which collective masks are produced from the aggregated biometric facial data of participants. The masks function as both a practical evasion of biometric facial recognition and also a more general refusal of political visibility, which intersects with contemporary social movements’ use of masking. My workshops are both site-specific, designed to engage a particular community in a specific place, and pedagogical, in that they educate publics on the often technically and bureaucratically complex deployments of surveillance and capture technologies. The project also offers people experiences in being together masked, which is certainly training in opaque ethics.

Zach Blas, Facial Weaponization Suite: Fag Face Mask - October 20, 2012, Los Angeles, CA.

The first mask in the suite is Fag Face Mask, which is a critical engagement with recent scientific studies that claim sexual orientation can be determined through rapid facial recognition techniques. During reclaim:pride, an intervention at the 2013 LA Pride in West Hollywood with the ONE Archives and RECAPS Magazine, the mask was used as part of a Face Face Scanning Station to performatively critique mainstream gay and lesbian politics’ desire for inclusion and recognition by the state.

Fag Face Scanning Station, reclaim:pride with ONE Archives & RECAPS Magazine, Christopher Street West Pride Festival, West Hollywood, CA, June 8 - 9, 2013.

Zach Blas, Facial Weaponization Suite: Fag Face Scanning Station, reclaim:pride with ONE Archives & RECAPS Magazine, Christopher Street West Pride Festival, West Hollywood, CA, June 8 - 9, 2013.

The second mask addresses a tripartite conception of blackness, split between biometric racism (the inability to detect dark skin), the favoring of black in militant aesthetics, and black as that which informatically obfuscates. Organized in conjunction with Ricardo Dominguez’s b.a.n.g.lab at UCSD, participants staged tableau vivants to dramatize these different yet overlapping shades of blackness.

Zach Blas, Facial Weaponization Suite: A Mask-Making Workshop, Performative Nanorobotics Lab, UCSD, May 31, 2013.

Zach Blas, “Militancy, Vulnerability, Obfuscation” Tableau Vivant, Facial Weaponization Suite: A Mask-Making Workshop, Performative Nanorobotics Lab, UCSD, June 7, 2013.

Zach Blas, “Militancy, Vulnerability, Obfuscation” Tableau Vivant detail, Facial Weaponization Suite: A Mask-Making Workshop, Performative Nanorobotics Lab, UCSD, June 7, 2013.

Such artistic practices demonstrate that at their core is an aesthetics that demands a different approach to looking, recognizing, and identifying, that confounds a standardized visibility structured by quantification, measurement, and reduction. These are withdraws from power through collective stylings but also occupations of zones that lie outside the perceptual registers of control. Informatic opacity, then, is not about simply being unseen, disappearing, or invisible, but rather about creating autonomous visibilities, which are trainings in difference and transformation. While such practices might remain utopic speculations or small-scale realizations, art makes the impossibility of informatic opacity feasible, practical, and fantastic, and its aesthetics omit something other than light that collectivizes and builds solidarity.

Endnotes

1. Alexander R. Galloway and Eugene Thacker. The Exploit: A Theory of Networks. (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2007), 131.

2. See Philip E. Agre. “Surveillance and Capture: Two Models of Privacy,” Information Society 10(2): 101 - 127, April - June 1994.

3. See José Esteban Muñoz. Cruising Utopia: The Then and There of Queer Futurity. (New York: New York University Press, 2009); Judith Halberstam. The Queer Art of Failure. (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2011); and Nicholas de Villiers. Opacity and the Closet: Queer Tactics in Foucault, Barthes, and Warhol. (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2012).

4. Ulrich Loock. “Opacity,” Frieze d/e. http://frieze-magazin.de/archiv/features/opazitaet/?lang=en (accessed July 15, 2013).

5. Irving Goh. “Prolegomenon to a Right to Disappear,” Cultural Politics Volume 2 Number 1: 97 - 114, 2006.

6. Galloway and Thacker, 136.