UnNCOMMON COMMONALITIES:

Aesthetic Politics of Place in the South Bronx

by Libertad Guerra

Building the Aura

Nowadays, aesthetic processes are sought to be projected into places, and not so much into time. Canon creation (i.e projection into time) is not the point anymore for cultural workers friendly to art world regulations. The 'canon' has become a dependent function of the success of tattooing a given aesthetic project onto space 1. That frozen representation of space, in turn, becomes the short circuit by which we decipher and generalize a place as totally entwined with its marketable projection.

BarrioBarrier- a concrete poem / banner by Edwin Torres -poet,

performer, Spanic Attack member. The duelling gang imagery

of the West Side Story narrative is represented by inverted

logos of the Sharks and Jets as

collision/dissolution of crude

oppositions.

Thus, at the level of city living and living cities, gentrification (bourgeoisified space) is aesthetically dependent. Neighborhoods do not gentrify these days without a specific kind of aesthetic footprint. When this type of socio-spatial filtering happens at a large enough scale we end up with neighborhoods and whole cities that bypass the un-monetized social need to adjust and breathe along its immediate surroundings. This partially explains the de-politicized condition of contemporary art 2.

Hence –for some time now- the configuration of creative clusters has been understood critically; for these clusters more easily become mechanisms for geographical displacement and consumerist overcrowding than nurturing drives that weave themselves into the wider fabric and uniqueness of the neighborhoods and regions in which they exist.

Because urban environments always adapt to demographic movements, the idea of mobility is taken as essential in the branding process of city neighborhoods; in this process the generic qualities of particular groups (their object-relations) get abstracted and then held 'for real'. This fallacy of misplaced concreteness obscures the ‘in between’ realization of such a relational event. Yet, gauging at how notions of center and margin remain static and are proselytized into our collective psyches help reveal the symbiotic pathos of creative clusters that adopt a mercenary relationship with places in order to consume and exhaust rather than sustain and build-up.

This, for example, explains why most mediatic interest in the South Bronx’s artistic scene (analogous to ‘artsy’ Williamsburg and Long Island City in its industrial infrastructure, accessibility to waterfront and immediate location to Manhattan) is intimately related to the speculative mindset regarding symbolically charged changes in retail and demographic morphology.

The anticipation of, say, the next Ikea and the hopes for a more ‘translatable’ (i.e. non-threatening) ethnic enclave activates much of the buzz surrounding the local art scene. In the contemporary artistic saga of the South Bronx, middle class expectations trump. Indeed, artists living in the South Bronx see their work rebranded by the mere fact of having moved here. They suddenly enter the curious category of ‘Bronx artist’. This area brands the artists as much as the outside expects them to re-brand the area. When the South Bronx gets into the mix, the main interest turns to its pre-conceived and perceived peripheral-ness. It is, first and foremost, an issue of spatial relationships; of the inside and the outside.

The neighborhood entices because it can ‘be had’ (consumed) at a representational level, but the outlook of 'having' (a presence of active qualities) is -most times- selectively amplified or carefully ignored 3.

Babel o city (the grand concourse of spanic attacks)

all politics is tics therein the polis all agitprop is props fed through gadgets sunscape matters inasmuch as shared summer matters inasmuch as shared a city is always inasmuch

When all meaning is placement and positioning, the most radical thing you could do vis-à-vis politics is to call these tics by name. For a cultural-political artist being ‘involved’ means –among other things- taking stock and approaching the latent issues in dis-place-ment conditions (diasporas, individual exile, peripatetic obsession) within the very social, collective and political logic to which they refer.

The idea is to carefully investigate these hypotheses by trying to exercise location not as a packaged product or a matter of real estate property, but as a relational network of differences and contested meanings that give form to a sense of intellectual and cultural property. When placed within a specific type of environment these inter-connective attempts to give form to a sense of the world relates to the field of aesthetics.

‘Spanic Attack, a South Bronx-based multi-arts collective, started as an initiative to engage with the artistic strategies that mainly Latinos and Latin American expatriates employ to appropriate operative socio-cultural terrains. In contrast to other areas known for their buzz-oriented cultural scene of transient residents, in the South Bronx we found ourselves working in and out of a borough best known for working-class immigrants, housing projects, and the outdated –yet, still operative- labeling of crime, arson and blight.

A conscious aim of Spanic Attack was to highlight the genuinely contemporaneous aspects of so-called peripheral zones and players (the periphery not as ex-otic and outside, but as concurrent) and discern truly contemporary creativity (regions of current projects in-the-making) from the reified bounds and set values of marketable design. From the outset the aim was to mix locally existing structures and symbols with resisting practices into an incoherent mass that would, by its very cacophony, disrupt the framing scale of the art field cultural economy.

Yet, the zeitgeist moves in the opposite direction. While looking for that set of unpredictable alignments (with different kinds of histories coexisting and decaying within the present) the prevalent logic of culture / knowledge workers, functions through nepotistic means that stresses submission to a mandarin hierarchy requiring relentless self-promotion and cynical entrepreneurship. Those whose energies are used to systematize micro-bureaucracies of self-promotion and shrewd in personal public relations thrive; those neutral or actively indifferent to symbolic currencies of the industry’s determined pace remain invisible. The norm is authorized criticism that fits into the territorialized art economy and frenzied tempo of programming demands. The cultural industry encourages creative types to validate what many set out to denounce.

Against the onanist logic promoting inbreeding and closed coziness, ‘Spanic Attack advocated moving along the lines of what Nikos Papastergiadis refers to when he writes that ‘a city’s creative potential can be defined by a calculus based on open and closed spaces, its cultural density is proportional to the multiple functionalities of the open space’ (Papastergiadis 2006).

Of Intros and Outsides

"New York been taken away from you…So my advice is: Find a new city"

-Patti Smith (Is Detroit the New New York?)

It is a commonly shared fantasy of many New York City residents (especially the panoptical creative class) to get the hell out (while remaining inside), when the tough gets going; to look for space and creative energies elsewhere while selling, promoting themselves and marketing here. To be out while occupying a dead footprint in the city. For creative types keep on hoarding and swallowing creative spaces (both literally and imaginatively) in the city; looking for the New York City artist dream without concern or regard to realities on the ground and histories of extant communities of artists and practitioners.

Presumably, the 'outside' is the mythical realm where optimal results can be achieved, purity is preserved, contestation is the most ethical, where the best karma is accrued and street cred is found. This is the outside-ism syndrome. A condition to which all cultural entrepreneurs and artists -yours truly included- have given in at one time or another. It is a protective drive towards remaining at the margins, at a critical distance, the pure perverse pleasure of opposition, or the joy of being detached and aloof. We live within a paradigm that holds that this very distance and outsider status is what supposedly fills things -art among them- with relevance. Yet, as we know, it happens that being outside creates a contrary -protective- logic of 'inside-ism' whereas groups that lie there want to self-perpetuate and conserve.

That openness and freedom from unhelpful constraints is many times believed to be outside. That was Patti Smith’s point, in the interview quoted above, when she said: "New York has closed itself off to the young and struggling,” (Kusisto 2010).

It, then, seems clear that the critical understanding of cultural dynamics today is pretty much mediated by the outside as both concept and positioning.

This utopian outside-ism might explain the plethora of social practitioners (many a group from Denmark's social aesthetics’ consulting industry) moving to Detroit -the very image of post-Fordist urban abjection and too perfect a metaphor for artistic work that rises from the ruins-, a place perceived to be smoothed out of pesky use value by entrenched inhabitants for newcomers to shape anew.

What will Detroit’s renewal outcome be: an ' in-the-making' model a la Boogie Down Bronx or the nondescript saturation of Alphabet City? The South Bronx and the Lower East Side were remarkably similar in terms of demographic composition and labeling as ‘Criminals Paradise Regained’ during the era of arson and neglect. Although virtually indistinguishable at a visual level -in its tenement decay, ethnic mix, fertile socio-artistic expressions - they developed differently. The ‘upgraded’ version of the LES (from Loisaida to the East Village) was achieved through the unrelenting scheming between city government and the real estate industry to oust locals who endured the worst years of disinvestment, yet had built the alternative housing, ecological models and socio-cultural dynamism (i.e. Nuyorican poetry, street theater, community garden movement) which gave the neighborhood much of its distinctive character. The dis-location process was helped in great measure by the cultural industry's mollification of what was the organic and potent merger between punk and hip hop sensibilities into all the branding possibilities of Street Art which muted the history and unpredictable collaborations on which they were forged. (many of those Outsider Art forms and genres ironically born in the S BX).

REFASHIONING: MODA (click on image to see expanded picture)

A collective art exhibit in tribute to Fashion Moda, the art space / cultural

concept in the South Bronx at the exact same address of its first location

(1978-1991). The project's main idea was to mix past and present history

of the space by displaying different types of art works by artist associated

with the original art space and a new guard of Bronx based artists without

interfering with the daily business of On Time,a Security Guard Training

School. Curated by Hatuey Ramos Fermin, a Spanic Attack collaborator.

Documentation of the project was part of

AVANT-GUIDE TO NYC:

Discovering Absence by Apexart.

Photo Credits:

Fashion Moda exterior, Spring Fever opening, 1982

(man and boy in foreground)

1982 LISA KAHANE, NYC www.lisakahane.com

2803 3rd Ave. Bronx, 2009 Hatuey Ramos Fermín www.hatmax.net

Designed by Hatuey Ramos Fermín

Moda’s Prosaic Poetics

“Fashion Moda in the South Bronx is the only alternate space in town that deserves the name it rejects”

- from Rejecting Retrochic by Lucy Lippard

This is where the story of Fashion/Moda can help as a pertinent methodological case-study and also a way of paying homage to past visionaries’ other kinds of efforts.

Founded in the South Bronx on 1978 by Stefan Eins, a Viennese artist with degrees in art and theology frustrated by the in-breeding of the SoHo scene, Fashion/Moda defined itself as a ‘cultural concept’, ‘a place for art, science, invention, technology and fantasy’. Joe Lewis, an African American artist, and William Scott, a Puerto Rican teenager from the neighborhood, soon joined as co-directors.

They concocted a street smart gallery space “devoted to experimentation, it changed the way that artists saw themselves and their audiences, and encouraged a special urban cross-cultural exchange. It opened door to many groups, including youth, police and local musicians. For the neighborhood it provided a new way of thinking about cultural venues.” (Hertz 1999)

As an idea, Fashion/Moda was a short-circuit. With a storefront on Third Avenue in the South Bronx, a location that Eins considered important because it reminded people that avenues did not end in Manhattan, it gained access to the most elevated circles of the international art-world, while operating from a dilapidated storefront in the South Bronx (at the time one of the most chaotic neighborhoods in the world). They refused to see those streets, buildings (even burning ones) and the neighborhood, as closed abstractions, stereotypes or clichés, but rather as processes happening right before our astonished eyes.

This experience on the edge became a refusal to neatly separate the Prosaic (from prose) elements of everyday life from its most Poetic areas. By collapsing the aesthetic experience usually sought in the professionalized art world with a quotidian strata that can be rife with invention, Fashion/Moda challenged the arbitrary and implicit consensus that sets art world boundaries into a quasi conspiracy (the ‘who’ and ‘what’ it actually consists of can be deciphered more through sociological frameworks than by normative pretenses). By intuitively apprehending the non-existent separation between art and everyday life, Fashion/Moda was able to enrich both.

Instead of downgrading art to include any everyday object, they elevated everyday life to artistic transcendence. Fashion/Moda’s puckish poetics evaded the jaded stance of making art relative to the ordinary; it actively penetrated the everyday with fantasy; brought forth the insight offered by the stereotyped masses; presented the individual meaning found in conviviality. Exceeding the rift between the initiated few and the unsuspecting many is what makes this organization stand out. The artistic avant-garde became more about being a frontier rather than an underground by introducing ‘the people and their world' as the necessary next perimeter of expression.

It seems clear that the South Bronx materialized, it still does in a different way, an area where everything could happen, where the process was literally up for grabs. Such a position could have taken the simplistic way out by glamorizing peripheral life and completely missing the point. These social ills may be a potential source of energy for the very process of creativity and self-examination; yet, they are not ends in themselves, they are the givens to be destroyed. The co-optable design of ‘ghetto-everyday-life-as-concept’ was not operative in this case because Fashion/Moda’s set-up of horizontal relations among individuals and groups could not be other than everyday life.

In addition to all its autonomous work as an alternative art place - Joe Lewis liked to emphasize it was not a ‘space’- Fashion/Moda was part of a network of community based organizations (dozens of them) that struggled within the South Bronx during its worst years of social and economic distress (Lewis 1999). When the Bronx started to come back to something resembling normalcy, it also started to lose its cachet in people’s imaginations. It is sad to say, but the South Bronx was the necessary no man’s land, a place without law, ruled by fear and treachery: a Nietzschean space fulfilling the psychological needs of the city and the rest of the nation. Why mourn Vietnam, if we had the South Bronx? Or why mourn the South Bronx if we have Detroit?

The demise of Fashion/Moda, they operated for about a decade, also shows how sometimes the beginning of an organic/un-hyped push back against neglect -the South Bronx moved itself away from its international metonymy/brand of urban decay- may signify the demise of an ethico-aesthetic movement. The neighborhood’s regeneration happened slowly and internally, without splash; it was change meant to be lived, not promoted in PR campaigns.

Without understanding the story and operations of an organization like Fashion/Moda it would be hard to see that contemporarily, as much as many cultural-political artists want to bypass clichés of ‘art rising from the ruins’ this is the herd mentality that operates, for it plays into the renewed discourses of urban transformation.

The attempt might be to build structures for inclusion, but there is always a strategic meta-audience in mind, those for whom culture is not a social good but an instrumentalized asset. Without the ‘educated’ spectator’s gaze to read the underlying repetitive patterns of the new economy, there would not be representational incentives to generate ideas that grow from specific places and muster the presence and range of social identities.

Going Places: Heuristic Stereotypes

If the aim is to learn something from our busted capitalist moment my point has been to rattle the stubborn symbolic order through critical examination of identitarian spatial tropes.

When we speak about mobile populations we refer primarily to two mobile groups: immigrants and mobimians.

The ‘immigrants’ are somehow bounded by the physicality of the infrastructure, moving inside the city space but in a parallel universe; the periphery in the center; the uptown in the downtown. Wherever they go, they uptown-ize the space. Many of them choose to simply call themselves migrants considering how un-viable getting a visa will be. They are the movable/shift-able uptown.

The ‘mobimians’ are the mobile bohemians; cultural entrepreneurs of Self, nomadic freelancers living in a phantasmagoric network society; the center in the center, the downtown in the downtown. Wherever they go, they downtown-ize the space. They are the movable/shift-able downtown.

So, we have either ‘uptowners’ or ‘downtowners’, (im)migrants or mobimians. Absent from this neighborly apartheid is the mythical figure of the mid-towner (and indeed, New York’s midtown is famously non-livable); the figure that bridges art and place, leisure and work, the artist-worker, or the worker-artist.)

If peripheries are literally swallowed up by the center, this spatial cannibalism suggests that migrants and mobimians do rub shoulders. Liberatory political artwork is to negotiate ideas of voluntary nomadism and necessity-based migration as the constructive creolization of other types/styles of sharing and production of knowledge.

Our mid-towner (what I propose) lives within a different understanding of space and time. This place-time is the city-instant; a place-time before and beyond the brand, below and above real-estate speculation. And thus, the midtowner's attitude is not a defensive wall, but a bulldozing soul. By merging the embedded intuition of the (im)migrant with the formalist disposition of the mobimian, there is an injunction that takes this aesthetic proposal beyond conventional geographic scales and zonings: “that of imagining a different reality while having your feet firmly on the ground”.

The Place in place of The Place

Henri Lefebvre once stated that “Against the shining progress of technology and commerce everyday life is a backward sector in the modern world”; an idea that his student, Guy Debord, would refine by positing that ‘backward sector’ as “a colonized sector in an affective Third world in the heart of the First.” That whole idea seems like an allusion to the South Bronx world-renowned status as the outsider inside the center of the world.

Lisa Kahane, a photographer, author and documentarian associated with Fashion/Moda, writes about these kinds of artistic transactions and movements (even if conditions in the area have radically changed her main insight applies): “The concept behind Moda supersedes its location in the Bronx, but the Bronx was its edge...Artists who came up from downtown had to step outside their comfort zone. A new and genuine local culture, once dismissed or reviled, passed through on its way around the world...”(Kahane 2008)

In the case of the South Bronx the question of ‘cultural projection’ is essential in our understanding of the creative processes in the neighborhood. The experiential situatedness within the icon (a place that is symbolically excessive: from bad rep, drugs, graffiti and arson, to hip-hop, community activism, the Yankees and popular aesthetics) makes it an ideal laboratory. With all its symbolic charge the South Bronx remains the place in place of the place 4 to operate in distinct (urban) orbits -from its Third worldliness to the First World city that (almost) contains it and into the transnational fold.

Ironically, the knowledge economy takes for granted that creative workers adopt saturated spaces; espouse the over-flow of prêt-a-porter meanings and operate in areas where ethnic and socio-economic dissonances are bracketed. There is a political comfort when development is tautological, spreads to docile contiguous zones, leads to the over-development of inflated rents, a repression of truly public space, and the socio-creative stagnation of being segregated. All at once, the process amounts to plain censorship by default, a mainstream joke of what the ‘up-and-coming’ urban neighborhood means.

To assume the cognitive liberty to explore enclaves beyond this bureaucratized and quick-profit speculative logic would demand a phenomenological shift in relational grounds that contains the potentially revolutionary results of an art with an intention.

Notwithstanding its objectively cheap(er) rents and geographical proximity to the ‘center’, the South Bronx is a tough sell for many; it is an unsettled point of suspension given its lack of standardized amenities. For all its cultural élan it is not art-marted but it is not in ruins either; a further disappointment on the ‘destruction porn’ front that boutique activism lusts after.

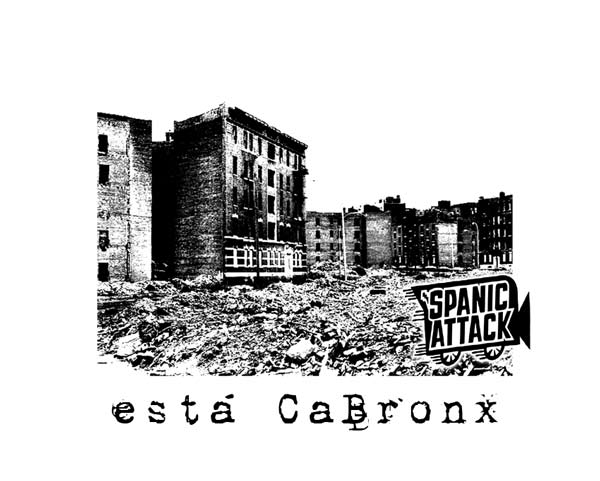

Image of a Spanic Attack T-shirt. The 'esta Cabronx' wordplay roughly translates to "the Bronx (B)rox!"

Our Uncommon Commonalities

Aesthetic value IS the insightful awareness of the social processes that underlie at the ground-level; understanding and using prosaics and poetics as an integrated whole. This insight corresponds with a heightened awareness that figures out the junction –both theoretical and real- between the urban ecology and the creative process, the historical links between a sense of self, broader ideals and the irreproducible local genius –that elusive vibe- of a place. Situatedness can puncture the self-referential bubble of rationalized place-branding, by permitting socially engaged artists to get close to things rather than judging from afar, or parachuting in.

I have tried to explore how, although radically peripheral still, the South Bronx is not immune to this logic. However, addressing ideas of mobility and migration as enplaced processes of construction, rather than of displacement and marginal resentment, forges a non-victimized peripheral-ness supported by intentional social relations in fluid informal arrangements. This sense of cultural and intellectual property should bypass the speculative logic that has privatized the downtown/center as if it were the only possible creative breeding grounds, and has frozen the site of artistic reception from functioning as a vigorous space for engagement.

Few neighborhoods have been so wildly projected beyond its boundaries as the South Bronx has; or fed so much its own image (sometimes developing into tragic self-fulfilling prophecies), while being able to keep reinventing itself both at a social, political and aesthetic level. A full sense of being at the center while being fully at the margins was Fashion/Moda’s commitment. ‘Spanic Attack’s backbone is a statement on how the South Bronx has been both the victim and almost completely in charge of its own myth, and how that continues to be the case.

Footnotes

1. Time is an agent inasmuch the temporal limit of an event modifies the self-contained venue but seldom is there spillover on to the street context of action-able everyday life through a changed framework that reconstitutes the stakes.

2. Boris Groys calls this phenomenon the age of touristic reproduction: transit artists who evade the pressure of local taste, rather than practice (a politics of the present) we embrace the politics of travel or nomadic life (Groys 2008).

3. Title of a poem by Urayoán Noel, from HI-DENSITY POLITICS, Blaze Vox books, Buffalo New York. Urayoán is a ‘Spanic Attack member. The following epigraph is also from babel o city.

4. Translation to El lugar en lugar del lugar, title of a 2008 Spanic Attack produced album by songwriter Rebio Diaz.

Bibliography:

Kahane, L. (2008). Do Not Give Way to Evil : Photographs of the South Bronx. Brooklyn, N.Y., Powerhouse Books.

Farmer, J. A. and Bronx Museum of the Arts. (1999). Urban Mythologies : the Bronx Represented Since the 1960s. [Bronx, N.Y.], Bronx Museum of the Arts.

Noel, Urayoan (2010). HI-DENSITY POLITICS, BlazeVOX Books.