Issues- Art Projects- Critical Conversations- Lectures- Journal Press- Contact- Home-

- Michael W. Wilson

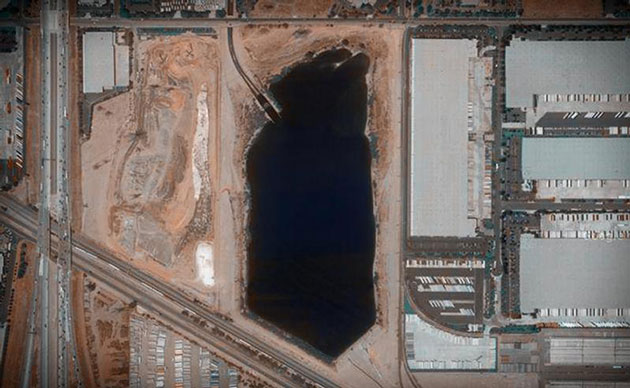

image: Black Hole of Mira Loma

#9

bios

buy

Our human nature is to lack trust in the things we can’t see. (The greatest example I know of is the

test of salvation, which requires an expression of faith in God whom we can’t see but whose work

is real.) Wherever there are places we can’t “see” inventory in the supply chain, we tend to order

excess to cover our lack of trust….Some players in the supply chain inflate order sizes to cover “unforeseen” circumstances that may occur in the “blindspots” or “black holes” in the supply chain

- Supply chain strategy: The logistics of supply chain management. New York:

McGraw-Hill, 2002. Print.

At the center of the Mira Loma, CA industrial district lies a large black pit. When scanning the area for distinguishing features, it serves to orient.1 It's the spiritual core of this particular 'sacrifice zone'—an area of ecological and social degradation resulting from unregulated industry and exploitation. Mira Loma sacrifices for the greater goods movement industry—the global supply chain of invisible labor. The invisible labor force toils in factories overseas, but also at ports, along rail lines, and in the many warehouses used to process the flows of commodities.

Mira Loma, home to one Superfund site and several other notable polluters2 , is a distribution hub located at the intersection of highways and rail lines in southern California's “Inland Empire” —the informal name for Riverside and San Bernadino counties—the more easily-exploitable populations adjacent to the (slightly) more organized LA labor force. In point of fact, names have always been important to the area. In 1930, the name of the area was changed from “Wineville” to “Mira Loma” after the infamous “Wineville Chicken Coop Murders”, in which three young Caucasians and one “headless Mexican boy” were murdered and disposed of in a chicken coop.3 In 2011, the residents of Mira Loma and several adjacent towns incorporated under the name “Jurupa Valley” in an attempt to regain some control from the logistics industry, becoming the newest city in California. In 2013, faced with a massive transfer of state wealth from local government to the incarceration industry, Jurupa Valley may become the most short-lived attempt at local governance in California history.4 Like most of the area, it faces a precarious future–it was built to serve a capitalist distribution system that has found new ways to cut costs by sacrificing the very workers who populate the areas in question. Recently, nearby San Bernadino became the largest California city to ever file for bankruptcy. The area has been ravaged by the last five years of economic decline—a cascading effect in which lower import volume removed the fuel for the area's growth. With the decline came austerity—removing most job security in the logistics industry and increasing the pressure on the labor force. This pressure to squeeze more profits out of labor resulted in a massive acceleration in the steady shift to temporary labor providers.5

Over 40% of all goods moving into the US are processed through the transportation corridor of which Mira Loma is a central link. Starting at the ports of Long Beach and Los Angeles, imported goods move by truck and rail into the Inland Empire for processing and distribution to retail locations throughout the United States. Mira Loma is a prime staging area for goods imported by big box retailers like Target, Home Depot and most importantly, Walmart.

Reporters covering the growing labor unrest routinely refer to the Inland Empire as "a series of warehouses"—conflating the geographical designation with its clear industrial purpose—as if the area were one vast commercial processing zone, devoid of human habitation. But this conflation has always been the plan. Riverside and San Bernadino counties were branded with the moniker "Inland Empire" by local boosters and developers nearly 100 years ago in an attempt to lure investment in a then nascent logistics industry. Since that time, local power brokers have siphoned off public redevelopment funds and manipulated zoning laws to create unregulated municipalities that catered to the growing logistics sector. With the exodus of manufacturing in search of cheaper production labor overseas and the accompanying global transportation infrastructure needed to handle such an increased volume of imports, large undeveloped areas were needed to receive, sort and distribute these imported goods. The Inland Empire—and Mira Loma in particular—were optimally-positioned to serve the purpose of processing imports for domestic consumption. Concurrently, real estate developers touted the affordable housing —recruiting the necessary warehouse workforce from the increasingly crowded and less-affordable Los Angeles metro area. What resulted was a vast industrial landscape—publicly-subsidized labor camps for the poor. A tragic inversion of such a camp appeared in the nearby town of Ontario in 2008, when those rendered homeless by the first waves of recession erected a notable tent city.

Just a few meters to the south of the black pit of Mira Loma stands a warehouse among warehouses. At one point, it was identified in all of the familiar search utilities as "Swift International". It's an appropriate but misleading title, as "Swift" owns the property and operates one half of the warehouse, but the other half of this warehouse is operated by National Distribution Centers (NDC) of Delaware, Inc. (branded as "NFI", and technically a subsidiary of NDC). To complicate things further, the workers in one half of the warehouse are temporary employees of an on-site staffing agency called Warestaff, LLC—and the entire NFI/Warestaff operation is directed by Walmart. Structurally, it resembles a classic criminal front—in which one operation trades openly while a shadier operation, under multiple layers of secrecy, lurks in the rear. This sort of shell game is typical of the current configuration of capitalist supply chains. Because Walmart can extract more profit and reduce its brand exposure within sites of maximum exploitation, it subcontracts the job—and its subcontractors hire subcontractors, etc. The result is heightened competition among Walmart's suppliers and downward pressure to lower wages, squeeze workers and ignore working conditions—the low-price guarantee at work.

In fact, managing the supply chain is key to the success of the large retailers who collectively preside over the circulation of global commodities. This circumstance is the result of an overall shift in production from the conventional “push” logic (dominated by manufacturers “pushing” goods into circulation) to a “pull” dynamic, dominated by retailers who “pull” goods when/where demand exists.6 “Pull” inevitably shifts power toward retail, because of their privileged (terminal) position within the supply chain—largely facilitated by data accumulation (via scanning technology) at the “point-of-sale.” During the crises of profitability that capitalists began experiencing in the 1970s, the field of supply-chain management became a key area of focus. By adopting distribution modalities and command-and-control concepts borrowed from the military (containerization and cybernetics) and efficiency principles pioneered by Piggly Wiggly (the Just-in-Time protocol later made famous by Toyota), retailers gained the strategic and tactical means to reduce the time goods spent in transit.

For the past several years, a group called Warehouse Workers United (slogan: “Uniting for the American Dream”) has attempted to address some of the most egregious state-side abuses committed in the name of supply chain efficiency. After years of OSHA violations, worker injuries, dehumanizing conditions, and precarious employment status, WWU initiated a series of publicity strikes and protests. In 2012, they organized a walkout at a Mira Loma warehouse, followed the next day by a 50-mile march from the Inland Empire to Los Angeles. The six-day march culminated in a worker-delivered letter (with more than 37,000 signatures) to the downtown LA office of Wal-Mart. Democratic party operatives and trade union bureaucrats then spoke to the workers at a “rally”. Unfortunately, such choreographed “disturbances” ultimately work to contain the labor threat, as their reformist demands for “better” warehouse jobs and conditions merely reinforce a completely unsustainable network of distribution.

image: flyer for Empire Strikes Back event

But such resistance is more than union-initiated reformism, saving workers in one part of the global factory, while shifting the burden to workers elsewhere—it's symptomatic of a much larger black hole-in-formation. The nature of the ‘Just-In-Time’ distribution model creates significant opportunities for disruption and failure--for ‘supply chain contagion’. As one industry analyst writes, “In a more complex and interdependent economy, fewer failures are required to transmit cascading failure through socio-economic systems...Thus we have problems seeing, never mind planning for such eventualities, while the risk of them occurring has increased significantly.”7 The invisible force that supplies labor to the global supply chain must become visible and autonomous--becoming a Black Hole Infrastructure or Base. But their external visibility will be strongest in the darknesses they create--through the blackouts, absences, disappearances and immobilities within the chain. This is where the sensible features of a struggle threaten to become revolutionary—as opposed to the labor union-initiated battles that force the struggle to different nodes.

As technology continues to provide capitalists with more options for goods movement, labor forces will continue to be squeezed and new zones of exploitation will be sought. Ports, warehouses, rail lines and other transport sites will become flashpoints simply because they represent, in the words of one industry expert, “perhaps the last frontier for major corporations to significantly increase shareholder and customer value.” Indeed, value is largely determined within these systems of circulation. The speed and efficiency with which commodities can be produced and delivered has become a determinant factor for gaining 'competitive advantage.'8 If these struggles can be connected and corridors of solidarity constructed, coordinated strikes from port-to-rail-to-warehouse-to-truck-to-store can be organized and joined. Black holes along supply chains can be pried open and flows can be interrupted, diverted and stopped. In this coming struggle, it will be critical to broadcast capital's instrumentalization of human, resource and environmental costs in order for struggles to begin connecting with a viral intensity. 9

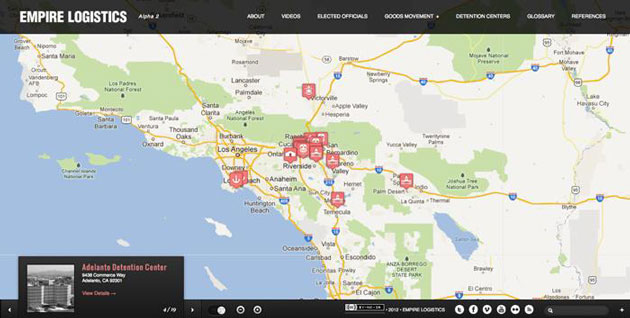

image: screenshot of empire-logistics.org

Footnotes

1. The pit holds effluent and industrial waste and is managed by the Philadelphia Recycling Mine - an industrial landfill operator. More information is available at http://www.chwmeg.org/asp/search/detail.asp?ID=850\

2.The Stringfellow site at 3490 Pyrite Street, Mira Loma is on the EPA’s Superfund National Priorities List - the most serious of all hazardous sites cited for cleanup. The Inland Empire has a total of three Superfund sites several leaking underground storage tanks (LUSTs) and many sites currently being assessed - including Philadelphia Recycling Mine.

3. These events formed the basis of the 2008 Clint Eastwood film Changeling.

4. Just two days before Jurupa Valley became a city, the California legislature voted to divert millions in vehicle license-fee revenue from local government subsidies to law-enforcement grants.

5. I came to study the Inland Empire during the five years I spent teaching in the art department at UC Riverside. I heard about the economic hardships being endured by my students and their families. They told of family members losing jobs, parents unable to make house payments and general financial distress. My own precarity as an adjunct lecturer in the UC system was a constant stress, but it seemed insignificant when compared to the layoffs, bankruptcies and foreclosures experienced by my students and their families. I began working with my classes to document the crisis facing the area in the Spring of 2009.

During one class focusing on research-based art-making, we compiled our research about the cultural impact of the crisis into a wiki.(http://classes.mwwilson.net/ctca/wiki/) During another class--the sort of technology class typically taught by adjuncts--my students learned 3D modeling by building proposals for public ‘sculptural’ interventions within the Riverside area.

I later became involved in organizing events meant to bring together UCR students with the various community groups affected by the crisis. http://occupyeverything.org/2010/empire-strikes-back-organizing-inland/

6. Bonacich, E, & Wilson, J B. (2008). Getting the Goods : Ports, Labor, and the Logistics Revolution. Cornell University Press.

7. Korowicz, David (2012) Trade-Off: Financial System Supply-Chain Cross-Contagion: a study in global systemic collapse. http://www.feasta.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/10/Trade_Off_Korowicz.pdf

8. Supply chain strategy: The logistics of supply chain management. (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2002). Print.

9. Over the past year, an autonomous study group has been meeting in the Bay Area to study the global supply chain. It’s composed of activists, longshoremen, academics, warehouse workers, artists, and others who seek to understand their place in the systems of capitalist production, distribution and consumption. The group is conducting workers’ inquiries, mapping supply chain nodes and studying the overall dynamics of 21st Century distribution. Group findings are being logged on the global supply chain research/mapping project Empire Logistics (empire-logistics.org).