Issues- Art Projects- Critical Conversations- Lectures- Journal Press- Contact- Home-

- Heath Schultz and Brendan Baylor

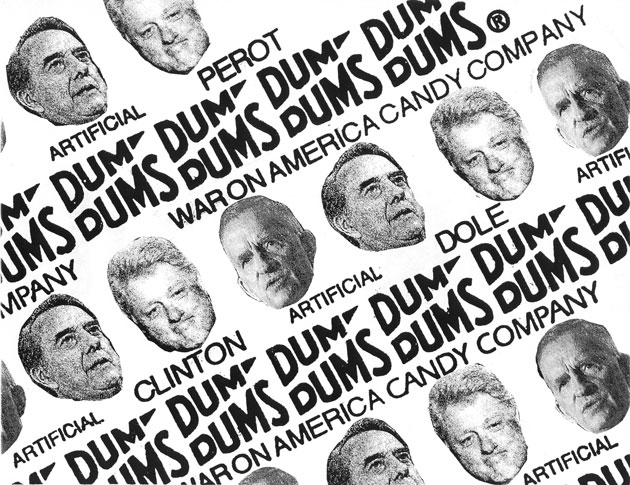

"DumDums" photocopy flyer wheatpasted in Boulder, CO in 1996.

Josh MacPhee is a member of Justseeds Artists’ Cooperative, Occuprint, Interference Archive, and has edited of a number of books including Signs of Change; Realizing the Impossible; and Signal: A Journal of International Political Graphics, among others. We met with Josh in February to talk about his recent projects.

Heath Schultz (HS): In many Justseeds projects, for example the Celebrate People’s History poster project, the group seems to have an implicit faith in the public sphere as a site of engagement. Is that a helpful way to frame Justseeds’ work?

Josh MacPhee (JM): I think we’re caught in a linguistic binary between public and private that isn’t representative of the world we live in. The private is the realm of the individual, and the public is the realm of the State. So it is question of sovereignty. What a lot of people are trying to do is create some sort of third realm, which for lack a better term would be the common.

HS: Right now it is a fashionable trend in Marxism to talk about the ‘commons,’ does that inform your understanding of the term?

JM: Thinking about the commons in relation to physical space comes out of my experience and attempts at historicizing street art in relationship to social movements. In that context the desire to control visual space does not seem meaningfully bound by the private / public dichotomy. To call temporary plywood construction barriers that have posters on them private or public space doesn’t really articulate the potential of what they are or could be.

We have no control over how the state functions or regulates our sovereignty; ‘public’ is like handing over our power to an entity that is nominally social but has no meaningful relationship to our communities. So my use of the commons comes out of a real practical concern.

I don’t know whether the common becoming the term du jour of academic Marxists neutralizes it or not. For a common to be enclosed by the logic of capital it has to be mapped, acknowledged, and understood. I’m ambivalent about this process and think it can be dangerous.

Brendan Baylor (BB): Is that a general observation or are you thinking of specific examples?

JM: I’m extrapolating from what appears to be a historical process. I’m interested in the ways some anarchist parts of 60’s counter-culture did an immense amount of mapping of the commons, or ‘social surplus.’ Groups like Provo in Amsterdam or the Diggers in San Francisco operated with the idea that in our relationships we create excess value, that we can have a world of surplus. Free food programs, the Provo’s white bike plan—these imagined a world in which anyone can get the sustenance they need and everyone can have a free transportation within their city or town.

But in the last ten to fifteen years, because of technological developments in network realities, there is an ability to map these relationships that create surplus value and then, through that mapping, to extract value. Provo and the Diggers’ projects have been picked up by venture capitalists as tools to convert that value into individual profit. Living Social, Groupon, Zipcar, AirBnB, and the shared bike programs—all of these things create the semblance of a social good, but all of it couched within the need to generate profit for a small number of people.

BB: Is thinking about the commons informing your shift toward more archival, curatorial, and design work?

JM: If we try look at things historically we see material spaces that don’t have a grand autonomy from capitalism, but rather are a conscious construction of physical and visual infrastructure from which to critique and engage with social inequalities and repression. This has been useful for the building of movements that attempt to challenge larger socio-economic structures. My interest in curating and archiving comes out of a long-standing fascination with history and my recognition of counter-institution building as a useful aspect of movement construction. But the counter part of institution building is very important—I’m not interested in building some simple non-profit entity. With Interference Archive we’re trying to figure out what it means to be an “archive from below,” both in construction and content, in organization and in funding.

HS: How does your thinking about an “archive from below” relate to counter-institutions, history, and other cultural practices?

JM: I’m generally distrustful of the “gesture”—a primary building block of the mainstream or status quo art establishment. Why gesture towards an archive instead of building one? The interesting part about it is what happens when it’s there, not what you a priori theorize about how it functions or doesn’t.

It’s great that artists can play with anything, but there is also meaning to be found in common definitions of what a collective is, or a cooperative, or an archive. Dismissing this does at least a semiotic violence to our shared understandings. If I’m going to call something an archive, to me, it should at least embody an honest attempt at being what most people understand an archive to be—a significant collection of contemporary and historical materials that are organized and stored in a way for them to be accessible and available for use.

BB: Could you talk a little more about what you mean by counter-institutions and what historical examples you might point us to?

JM: The Interference Archive is both positively and negatively modeled off a lot of existing institutions—some of them very professional and others DIY. The commitment to having a meaningful collection comes out of seeing the level of responsibility that more institutionalized archives have given to their collections. Places like the International Institute for Social History in Amsterdam. When the Nazis were about to invade the Netherlands, they put a significant portion of the collection on boats and shipped it to the UK so that it wouldn’t be destroyed. At the same time the desire to have an archive that also functions as a social space is a negative reaction to existing institutionalized archives. We wanted to create something that has some of the spirit of the old info-shop, or a European social center. We want to merge that social functionality with the idea of the past being important, and that the material culture of past movements is a useful tool for understanding who we are and where we may want to go. Seeing institutions like the Lesbian Herstory Archives in Brooklyn, or the Freedom Archives in the Bay Area, both of which are very much rooted in and developed out of specific sets of politics and are driven by concerns that are embedded in the histories and politics of the people involved.

Radioactivity! Anti-Nuclear Movements from Three Mile Island to Fukushima, exhibition at Interference Archive, October 2012

BB: Let’s shift gears a bit: as a printmaker I’m curious how you decide which prints are unlimited v. limited edition hand or wood block print. Is that an aesthetic or tactical decision?

JM: I didn’t come to printmaking through formal training; I came to it through a combination of street art, stenciling, and Xerox zine punk flyer creation. So more than the craft of printmaking, it was the engagement with the multiple that was the functional part for me.

So much of doing those things was deeply embedded in being part of a subculture, and so for my generation and a lot of the people of Justseeds, the quality of that kind of printing became a visual short hand for a whole larger set of ideas—it meant that you were some variation of anti-capitalist or challenging of the status-quo, that you rejected what mainstream society said was the way that images should be produced.

BB: You’ve spoken before about a desire for an un-alienated cultural production, or at least less alienated. Does hand printing fulfill that kind of desire for you?

JM: Yeah. I’m not sure that I believe any of that anymore. [Laughs] But it is a nice theory. I actually think that what happened was that there were material and quantitative limits to the way that we could produce things and then we turned those into qualitative values. There are good things that come with that, but there are also downsides—it perpetually positions you on the margins and it often limits your audience.

I’ve gotten to the point where I enjoy the practice of printing but that is a personal enjoyment and not a political statement; or if it is a political statement it is not one I feel particularly attached to making. It turns out that I can do large-scale runs of mechanical offset printed posters, and most people don’t notice the difference between this and hand produced screen-prints.

HS: What about the ways print is fetishized on the left because of its residual radical past; is this why some folks still have an attachment to hand printing? Does this sentiment linger in some of Justseeds work?

JM: It seems like hand-printing has really jumped back in vogue, but it is hard to know how much that has to do with the specific qualities of print and how much it has to do with capitalism’s descent into creating markets for every possible micro-desire. Everything is “in,” there’s nothing that’s not in right now. There may be value in trying to dig specifically into why print is making resurgence, but I also think it can’t be divorced from the need of the larger socioeconomic system to activate every potential desire in order to extract value from us at all times.

BB: I want relate this to what in the art world is has become known as “interventionist” or possibly “social practice” projects. Do you find any value in the space that’s being carved out by these practices?

HS: I would add that one could put Interference Archive in those categories if they wanted to. It also could be one way to tie a thread between many JOAAP readers and connect some of the divergent spaces you inhabit that usually exists outside academic contexts.

JM: I understand the turn towards social practice or relational aesthetics as being an engagement with the relationships between people and those relationships as being the medium for a kind of cultural practice. One of the things that come with that is to still see those relationships as an art gesture, and the goal is to have a successful gesture. As a joke I sometimes say that I believe in socialist practice, not social practice. What’s at stake at the core of that practice is not just the relationship between two people, but making those relationships more egalitarian.

Book Bloc making workshop with striking Cooper Union students, April 2013

HS: This leads into a big question about the utility of the academy, and if the “accessibility” of something like Justseeds or Interference Archive is perhaps more useful because it functions in a more practical way. Obviously this is entangled with the increasing problems, and arguably increasing bankruptcy, of the university.

JM: I almost always do things for a general audience—I don’t see the art world as my primary audience and I certainly don’t see academia as my primary audience. What I realized, partly because I didn’t go to art school, but also by engaging in a lot of different audiences and communities, is that people within the arts tend to have an extremely inflated sense of their own importance in the world, and that most people don’t give a shit about “Art.”

The question is how can you or I or we figure out non-marginal ways of communicating in less alienating forms that is not completely antagonistic to our other goals. You mention interventionism—in the larger art world, the critical wing that’s practical and activisty, there’s a real split between the work that is spectacular and the work that definitivelty isn’t. For the spectacular wing, the goal of any project is ultimately to create a giant splash, to get mainstream press, to become visible to a broad audience, if only for a moment. Although I respect a lot of what the spectacular camp does, I’m not interested in it at all. Usually it is completely destructive to the groups that I work with because it changes our relationships to each other and to the larger world in ways that are extremely short term and negative.

HS: So by “spectacular” you are talking about a Yes Men or Stephen Duncombe style of cultural engagement?

JM: Yes, I like Stephen a lot; I think a lot of the things he’s said and written about are really useful. I also think some of the Yes Men actions have been extremely effective and useful. But for my own practice I don’t find the spectacular action to be fulfilling. Change comes from people having meaningful relationships to each other, and those relationships aren’t built on the edifice of mainstream news and information distribution. It’s one aspect of larger campaign work, but when it becomes the central goal then it gets dangerous. In cities like Chicago and NYC you get into situations that have been happening since the ’70s where you get unions who work with the police to orchestrate public arrests so they can get on the evening news, and it becomes this whole package deal.

HS: Another significant part of your work is collaborating with movements external to Justseeds and Interference Archive. For example Occuprint, which is a website that sort of acts as an archive and distributes posters related to the Occupy movement; or the Justseeds portfolio projects—a series of prints created by Justseeds for a particular activist organization. Justseeds has done portfolios with Iraq Veterans Against the War and Critical Resistance, among others. How do these collaborations relate to your personal archival and curatorial work?

JM: The portfolios are a direct crib from the Taller de Gráfica Popular, a Mexican print making collective that came out of the Mexican Revolution with the idea of producing popular graphic works that exist in multiple forms. Through the act of making a portfolio we’re producing a set images that can be used on the ground by activists, can be reproduced and distributed inexpensively, can be shown in exhibition form, as well as republished in print and online. Simultaneously the portfolio can exist as an art object which functions as a fundraising mechanism for the organizations that we work with, as well as for ourselves.

Since the ’30s/’40s, the last time that there was really a mass Left in the US, there hasn’t been a particularly formalized or even inventive non-formalized way for cultural producers to engage with movements. Those relationships have become more and more stagnant, stuck in ways of working that don’t relate to the contemporary realities of either the movements or the artists. An unintentional effect of the demand in the ’30s of the only ever-existing artist union in this country for artists to be recognized as workers is that artists came to be seen as service providers to movements. Rather than actually being part of the development of the politics that we are engaging in, our engagement as artists is compartmentalized by our relationship to and through a wage. That became worse in the ’80s and ’90s when unions and community organizations started hitting budget crunches and artists were expected to have a wage relationship but not even get the wage. The ghost of that still haunts those relationships but it is starting to change.

If we want to argue that culture is integral to social transformation, that means that the people producing it need to be integral to the production of the politics that are pushing that social transformation rather than just ancillary. That responsibility goes both ways.

More recently I’ve been thinking about things in terms of short-term/long-term and deep/shallow. As access to the means of one’s own reproduction become more precarious and seemingly more scarce, then the pressure to make decisions to invest in your own personal good in the short-term over the greater social good in the long-term get greater and greater. So for me, both Justseeds and Interference Archive are attempts at privileging the social and the long game over the individual short-term. They’re about trying to figure out how to build social bodies that are about figuring out how to solve problems within a group, rather than always externalize them onto individuals. From how to be politically effective to how be a successful individual, ultimately these are social problems.

HS: Before we sign off we are curious if you want to talk at all about the [2012] Creative Time Summit and your quasi-participation in it. I think it is an interesting example of problems that are always latent so many events we participate in. Your response was interesting and was probably challenging for people on both sides.

(Note: Several artists who were scheduled to present or perform boycotted the Creative Time Summit entitled “Confronting Inequality,” held in NYC October 12-13, 2012. Egyptian media collective Mosireen sent a call for participants to boycott the Summit due to Creative Time’s partnership with the Israeli Center for Digital Art, an organization who has not condemned the Israeli occupation. While the ICDA did not receive money from Creative Time, they were partners in screening the summit as well as facilitating discussion, and thus implicitly endorsed by Creative Time. During Josh Macphee’s presentation (available here: http://creativetime.org/summit/2012/10/12/josh-macphee/), he did not discuss Interference Archive as planned, but instead problematized individualized boycotts in favor of social ones, and offered several local NYC resources on the Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions (BDS) organizing efforts for those who wanted to learn more.

Mosireen’s original call to boycott can be read here: http://mrzine.monthlyreview.org/2012/mosireen091012.html, and an updated post about the events at the Summit as they relation to the call can be read on the blog hyperallergic: http://hyperallergic.com/58499/artists-cancel-their-creative-time-summit-appearances-over-controversial-israeli-partnership/)

JM: [Pause] That was a difficult issue/reality to negotiate. I said most of what I wanted to say in my actual talk. I believe that most people like to get up in the morning and think that they are moral beings, and that they make decisions based not only on what benefits them but also in try not to do harm in the world. Unfortunately these two things are sticky, and we can't always have it both ways.

If you are going to have an event and call it “Confronting Inequality,” then you can’t have a series of artists pull out—for reasons which raise a significant specter of inequality—then pretend the problem doesn’t exist. When we got close the end of the Summit and almost no one had directly and clearly explained why artists were boycotting the event, I decided I should forgo my prepared talk in order to try to explain the Palestinian call for BDS, and why it is important to grapple with. To me trying to deal with and negotiate that is far more interesting and important than having a successful art event, or building your career. That’s the stuff of life; these are the questions that everyone has to deal with everyday. That is what art should be dealing with.

HS: That is why we wanted to re-visit it and look at it more closely. I wasn’t there, but from FB messages and blog posts it seemed like a non-event, and that kind of baffles me. Though there were exceptions, most people seemed to not care about the call to boycott from Mosireen or when presenters and performers dropped out.

JM: I’m not entirely sure [pause], I feel like there are larger ontological and spiritual questions about the nature of art in our society. I think part of the reason why these things seem like non-events is because we’ve reached an endpoint where almost no one that is not directly invested in art in relation to their own reproduction gives a shit about it. Yet at the same time there is no shared public acknowledgement of that reality. On the one hand we want to pretend that having our own personal political art Ted-talks is meaningful in the broader world, and on the other hand we don’t want to then deal with the fact that the format and structure don’t seem to be engaging to many people. It’s telling that when I called Palestinian BDS activists to get advice about what to do at the event, they hadn’t even heard of it, and in general spend almost no energy on the visual art world.

It was interesting to see that so many of the luminaries of the political art world—both artists and theorists—who spoke at the Summit didn’t even mention that a protest was happening. The more cynical side of me wants to chalk that up to a fear that doing that would get in the way of their own careerist ambitions, and then the less cynical side of me thinks they were just more honest about the limitations of the form. I’m not sure what my disobedience accomplished, but it has started me saying: “if you can’t bite the hand that feeds, then what hand can you bite?” [Laughs] That seems like a decent thing to keep in the back of one’s mind while going through life, because in all likelihood the hand that feeds is not particularly benevolent.

One of the best things to come out of my experience at the Summit was that it pushed me to travel to Palestine. In June/July of 2013 I went to Palestine and Israel with a group of archivists and librarians. We have formed a solidarity organization called Librarians and Archivists with Palestine, and are actively trying to figure out how to support—both over there and at home—the work of Palestinian information workers. More information can be found at https://librarians2palestine.wordpress.com/.

Justseeds' IVAW portfolio being hung in the street