Patainstitutional Inquiries- Issues- Journal Press- Contact- Home-

Three metonyms for Critical Practice:

Jig, Foam and Yield

Marsha Bradfield, Amy McDonnell, Neil Cummings

Abstract

This tripartite account reflects on the patainstiutional approach of Critical Practice Research Cluster (London, UK) in which three long-standing members evaluate the event of #TransActing: A Market of Values (2015). #TransActing was the result of a five-year period of research into value, values and forms of evaluation, which culminated in a bustling marketplace nurturing and celebrating economies other than the competitive markets that dominate contemporary life. There was a tear seller, various skillshares, an alternative art school, organ donation, permaculture advocacy, a freegan food cafe, a speaker’s corner, a listening stall and multiple currencies in circulation. Together with a milling crowd, stallholders creatively explored existing structures of evaluation and actively produced new ones. A trio of metonyms surfaced during the making and realisation of this project, ‘jig’, ‘foam’ and ‘yield’. Cluster members Neil Cummings, Amy McDonnell and Marsha Bradfield reflect on these metonyms to examine the patainstitutional framework of Critical Practice as a dispersed, flexible membership of artists, designers, curators, researchers and others working together as we try and avoid the passive reproduction of art and uncritical cultural production.

Introduction

As a patainstitution, Critical Practice Research Cluster relates to but also outstrips many conventions of academia and other norms of institutional knowledge production. We do so with one foot inside Chelsea College of Arts (University of the Arts London) as the other foot reaches beyond into other fields of enquiry (economics, sociology, technology and more) with a membership that also extends past the bounds of the art school. Straddling overlapping fields, Critical Practice pursues collaborative practice-based research. We recognise this as ‘pata’ because it bucks traditional organisational structures in its emergent and pragmatic modes of self-organisation.

Since its founding in 2005, the cluster have followed the protocol of ‘open’ organisations, a tech approach drawing on open source (in which all content can be modified, shared and is made public) that intends to produce a decentralised, accountable and responsive structure of individuals working together (P2P Foundation 2006). We post all agendas, minutes, budget and decision-making processes online for public scrutiny and our research, projects, exhibitions, publications and funding, our very constitution and administration, are legitimate subjects of critical enquiry (Critical Practice 2017).

Members of Critical Practice assembling trusses coordinated by a jig. #TransActing; a market of values, July 2015

Critical Practice has been practicing during a very particular moment in time when the political within economics has been exposed more than ever. The cluster was still in its first few years when the financial crisis hit in 2007-8, which different members of Critical Practice would argue has influenced our matters of concern in various ways. But what can be agreed upon is that Critical Practice has dedicated much of its energy to concepts of ‘publics’ and ‘being in public’. We have a longstanding interest—more than a decade—in public goods, spaces, services and knowledge and a track record for producing original participatory events. These exemplify the spate of artistic and cultural activity in London that has been committed to critiquing the institutions of the cultural sector. Consider Art Not Oil or the Precarious Workers Brigade, who use strategies to combat issues such as gallery sponsorship and the plight of workers in cultural institutions from underpaid cleaners to interns. Although Critical Practice focuses on active practice-based research rather than activism such as direct action, its patainstitutional structuring and functioning as well as its dedication to areas of focus that bat against privatisation and unscrupulous marketisation, speak of a sustained critique shared with these other forms of engagement.

In this text, three members of the cluster discuss #TransActing: A Market of Values (2015), the flea market-like event comprised of ‘stalls’ that featured artists, designers, theorists, philosophers, civil-society groups, ecologists, enthusiasts, experts, activists and others. The reflections on this event that are shared here find form as a tripartite text that expands three terms that were emblematic to the project. ‘Jig’ narrated by Neil Cummings represents reflexive engagement with self-organisation, ‘foam’ is a flexible form of social composition depicted by Amy McDonnell and ‘yield’, elaborated by Marsha Bradfield, is described as both the bounty of value that accrues and that gives way as it is redistributed through co-production. This multi-vocal account of #TransActing might seem unorthodox, but in fact it is a good representation of the organisational methods of Critical Practice itself. Rather than perform with a cohesive, collective voice, self-organisation is composed of a looser ‘cluster’ of individuals. Projects are proposed and then require others to demonstrate their enthusiasm and commitment to make them happen. Therefore it seems apt to maintain differing accounts of #TransActing, united in their purpose and strengthened through difference.

Jig

Narrated by Neil Cummings

During the eighteen-month-long development of #TransActing, a working group formed around the production of ‘stalls’ that were to compose the physical infrastructure of the market. To embody our interest in resilient evaluative practices, the working group aimed to recycle materials from what would be the de-installed 2015 degree show at Chelsea College of Arts. In previous years, a suite of refuse-skips collected unwanted artworks and trashed exhibition-making materials: timber, boards, furniture and other unloved things. We aspired to repurpose what would otherwise be ‘waste’.

While collaborating with architect Andreas Lang and others at public works, Andreas introduced us to the autoprogettazione furniture series of Enzo Mari from 1974. The series uses standard timber sections to produce a range of tables, chairs, beds and bookshelves. The plans, with dimensions and a cutting log for the furniture, were also freely published in a premonition of a Free Libre Open Source Software (FLOSS) ethic, and a gesture towards a cultural and material commons (Mari 2002).

At a trial workshop, taking Mari as our guide, we salvaged materials and set about measuring, cutting and screwing prototype stalls together. It became obvious early on that we would need a simple means of coordinating all the complex elements of the construction process: we would need ‘jigs’. A jig is a custom-made tool used to coordinate the location of components and the actions of people. The need for jigs arises when there are various vectors intersecting, in our case these included: the need to produce many stalls in a small time-scale; not knowing with any confidence who and how many people would volunteer to help; our need to make use of recycled wood in different sections and lengths; the black hole that was the skill base of the volunteers; a limited resource budget, and so on. I began to think of #TransActing as a patainstitutional platform and that during its production it would enable different individuals, groups and evaluative communities to be in exchange.

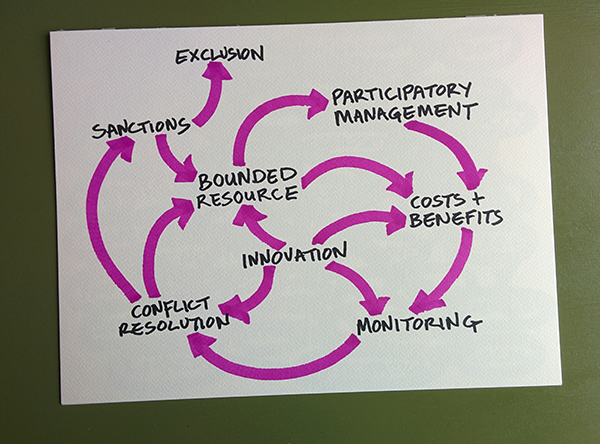

Nested polycentric governance; tracing the protocols within Critical Practice

In previous development workshops for the stalls, we had refined our stall designs (based on an Enzo Mari table) to basically three types—bench, table, stall—and each one could be produced from a selection of five standard components with each component requiring the cutting, assembly and screwing of approximately nine elements.

We salvaged a variety of boards, fixed them as tops on improvised work tables, and on them made one-to-one drawings of each of the five components, these were: three different leg heights and two lengths of connecting truss. We then set about screwing scrap wood to the drawings to act as guides, braces and stops to aid the location of the elements necessary to fabricate these stall components. These were of varying depths, as some elements were laid flat, others butted and some crossed over. Eventually, we had five jigs.

Once assembled, we put them to work, laying in pre-cut elements to screw together, and then prised out in the first trial assembly of a ‘table stall’. The trial was to make sure that the measurements and tolerance of the jigs were sufficient for the build ahead. A few tweaks and they worked; they worked very well and were, by rough consensus, approved.

The jigs proved key to producing the volume of stalls necessary for the market—nearly sixty. For this to take place some additional timber sections, 65 tarpaulins and mountains of screws were ordered. We organised a common tool bank from our collective tool kits and signed-up for daily working groups during the construction period. The jigs had enabled a group of people to make the first stall, who now in turn had the knowledge to instruct others. They became working group coordinators capable of inducting new members to the jigs, as well as the elements and processes necessary to make components, and to be able to assemble any of the three stall types. As determined by the jigs, we began to classify our waste materials into section types; we removed screws and nails, and with a chop saw set about pre-cutting elements, stockpiling them for use. The jigs were organising materials and, in turn, began to assemble individuals into groups, and coordinate their actions. The jigs were producing rich collaborative encounters.

I could see that the jig was a tool, but also a kind of protocol, like the published protocols—mission statements, aims and objectives, constitutions, rules, employment guidelines, terms and conditions, etc., that facilitate and organise any network, group or community. Critical Practice for example, uses Guidelines for Open Organisations (P2P Foundation 2006) to facilitate and coordinate the activities of our self-organised cluster. Protocols emerge whenever there is a deliberate organisation of interactions between people and Guidelines for Open Organisations, for example, encourages all decisions, processes and production to be made publicly accessible and transparent. That’s why Critical Practice uses a wiki to archive itself. The jigs were equally 'open'; simple to use, accessible and were able to organise and discipline—try putting an over-long length of timber into a jig, or screwing elements together in the wrong sequence—impossible. The jigs were physical protocols, which produced assemblies from disparate individuals, materials and resources and coordinated their interactions into collaborative communities. The jigs were relational machines.

Some people who volunteered to build the stalls were able to commit to the whole construction period, others a daily lunch hour, some a morning, others a few afternoons and some just joined in as they passed by because it looked fun. Some people were carpenters, others were confident in their craft skills, others unconfident and some thought they knew nothing. Some people understood the design and logic of the stall construction, others had no knowledge of #TransActing, the stalls or our intention. Yet the simple jigs, like the Guidelines for Open Organisations, easily accommodated all these differences and made every contribution (in terms of time, attention, skills, care, desire, etc.) no matter how small, productive. The jig formed friendships, coalesced solidarities, enabled skills to be shared, instructed and triggered enjoyment.

As we each contributed to the assembly of our first stall, a slight glow of pride was followed by an intoxicating buzz of excitement. This was fun, and it was really productive. Simple creative interventions or hacks, both material and inter-personal —political even—emerged, were modified and put back to work. These hacks, like putting packing-pieces between the jig and components to make for a tighter truss assembly, revealed and enabled a means of accounting for actual moments of creative cooperation. Moments when two or more people have to negotiate rather than merely comply with instructions or protocols, coordinating their actions and work together to produce something for others, something that others could benefit from, something like a community. The jigs as relational machines produced temporary self-governing communities. People moved fluidly between the communities, contributing where necessary; assembling legs, making trusses or assembling completed stalls. When new volunteers turned up, they could be quickly inducted into the process, learn the simple skills and contribute.

Throughout the production of #TransActing, we discussed reusing the stalls for other things after the market day. Too often in ‘art’ projects the incredible labour necessary for up cycling and producing things for exhibition results in little more than a temporary spectacle and, moreover, one destined for waste or landfill. To be true to the values we valued, we made provision for the stalls’ afterlife. By sawing off the stalls’ roof supports, they were transformed into sturdy Mari-like tables. For several months many were dotted around the Rootstein Hopkins Parade Ground providing much-needed public seating and tables for working, lunching and socialising. Other stalls found new homes in studios and offices around the campus of Chelsea College of Arts. Several went to an anti-gentrification project in Deptford, some to a community garden and others were sold to a pop-up restaurant.

Foam

Narrated by Amy McDonnell

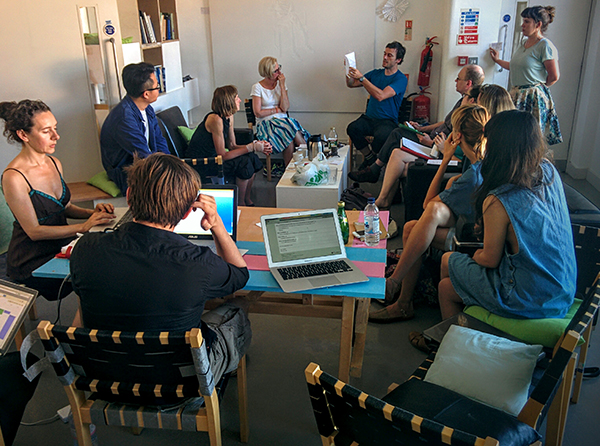

Critical Practice Working Group meeting for #TransActing: a Market of Values. July 2015

As Neil’s jig account suggests, design played a key role in facilitating the space for collaboratively building the market stalls. Coming together with public works, we began with the anti-industrial, easily made designs of Enzo Mari, which he circulated free of charge for anyone to replicate, copy and adapt. If foam is accepted here as a metonymy for this activity, what are the potential wider outcomes of designing foamy spaces such as #TransActing and other temporary platforms that accumulate in a surge of energy and then rapidly diffuse, its elements repurposed? Do these efforts also burst with the end of the project? Designer Ezio Manzini says that, ‘to take decisions in a designerly way can be used for collective living’ (Manzini 2015). He views the role of design as crucial; the designer’s critical ability, creative problem solving and pragmatic solution taking are all skills that can be channelled towards finding ways to make society more sustainable, more resilient. In an age of environmental crisis caused by the neoliberal market’s continual drive to scale up, which indiscriminately uses up natural resources, there is an obvious requirement to rapidly rethink the way we approach the organisation of global exchange; the production of our values through these exchanges; and the way we set protocols to arrive at decisions about a collective future. In keeping with Manzini’s thinking, bottom-up approaches such as #TransActing function as prototypes that can be adopted and adapted. They constitute, ‘a possibility to see a different notion of infrastructure seen as a network of small things. And this is going to change the very old idea of the economy of scale, that to reinforce yourself you have to grow’ (Manzini 2015). This is the stuff of patainstitutional organisation, the dispersed, cooperative spaces that act as testbeds for ways of working and living, that allow diverse communities to connect without the central power systems of traditional institutions, whether financial or otherwise.

In Together: The Rituals, Pleasures and Politics of Cooperation (2012) Richard Sennett writes that by producing forms of precarious, individualised labour and growing financial inequality, our current economic system inhibits forms of collaboration and, in turn, causes social anxiety. The conditions of the contemporary labour market encourages a more individualistic mode of working and, in Sennett’s language, actively ‘deskills’ society in the practice of cooperation. Sennett, like Manzini, points to the challenge of living together in diverse communities as one of the main issues of today and sees the workshop as a model for relearning these skills, as a site of experimentation and collaborative creativity, where habits are developed and re-learnt through the purposeful, rhythmic repetition of making. Cooperation must be crafted through critical thinking, labour, skill and willing diplomacy. These workshop habits and behaviours were adopted while building the market stalls for #TransActing; it seemed like an experience that is all too rare. Collectively coming together to problem solve, think creatively and respond pragmatically, seemed like a ‘natural’ thing to do.

Each morning we would arrive to the smell of sawdust and lines of, as yet, uncut timber, taking turns to saw, drill or hold steady planks of wood in the jig to ease someone else’s work. Stopping for lunch together felt important, to take care of ourselves and enjoy the food was an act that solidified whoever was a part of our ever-changing group of builders. Despite the seeming ‘naturalness’ of this daily rhythm, this environment did not arise as spontaneously as it felt. A diverse skillset as well as the inclusivity and awareness of others came from years of Critical Practice learning how to work together and how to function as an open organisation; individual’s knowledge and practice in administration, catering, collaboration, craft, design, diplomacy and more; constructing a wider network and good working relations with, for example, public works and Chelsea College of Arts; and of course the jig, made to enable the construction of market stalls based on the Enzo Mari autoprogettazione designs. The ability to craft cooperation is to understand and nurture all of these different elements that allow for a platform, such as #TransActing, a facilitated open space, to occur. Manzini calls this activity a ‘distributed system’ and writes about the benefits of such organisational frameworks:

In the distributed system, to reinforce yourself you have to have better links. So the small is not necessarily small when you are in a networked society. This increases the networked resilience of the system, in general vertical systems are more fragile and the horizontal ones are more resilient. Behind the scenes of these small groups of social innovation, we can start to see something that is a new environment, a new eco-system, that could be based on the potentiality of the distributed system’ (Manzini 2015)

Foam shares this seemingly scattered, and therefore seemingly precarious organisational form yet, ’this restlessness has a direction: it leads to greater stability and inclusivity. One can recognise old foam by the fact that its bubbles are larger than young foam… An aged foam embodies the ideal of a co-fragile system in which a maximum of interdependence has been achieved’ (Sloterdijk 2016, 48). We can say that distributed foam spaces are more resilient than chain, or vertical ones in the way that they can structurally sustain themselves (as if there is a glitch in one element in a networked structure—or indeed if a bubble bursts in a foam—another route can be found or the remaining bubbles will shift and rearrange to accommodate this change) and as they are more sustainable, as foam structure moves away from the logic of scaling up and the erroneous thinking that, ‘nature is limitless [...] we will always be able to find more of what we need and that if something runs out it can be seamlessly replaced by another resource that we can endlessly extract’ (Klein 2011, 32–33).

Platform and networked models have proliferated in multiple aspects of contemporary life regardless of ideology and the consensus-making database. Blockchain is an interesting example to take up here, as it could well have been represented at #TransActing as an alternative form of exchange. It sets up a protocol for transacting online that removes ‘the middleman’ and supposedly the ‘messiness’ of human decision-making that can lead to corruption. Blockchain is perhaps best known for supporting Bitcoin and other cyber currency transactions without the need for banks or other centralised organisations to carry out and verify monetary exchange. Instead, computer networks, or communities of nodes, can automatically take these actions. The more nodes in a particular Blockchain community contributing to this verification, the more effective the decision-making process. When a block is proposed (i.e. that a piece of data is worth X and should be transacted between Y and Z), if the majority of nodes agree (for example that this is an amount worth X and that it has not been transacted before), then this exchange will go ahead, regardless of whether one or some of the nodes are ‘acting out’ or disagree. The majority wins and the proposed data block is copied and added to the informational chain shared by all of the present nodes.

However, as researchers and Blockchain innovators Jaya Klara Brekke and Elias Haas point out, although this is an exciting, new way to share and collaborate without centralised power structures, it does not mean that this space is necessarily completely ‘open’ to all and free from power dynamics. They ask the question: ‘What exactly is being disintermediated? And is there in fact an equally strong re-mediation taking place?’ (Haase and Brekke 2016). Jigs, platforms and other forms of distributed organisation dissipate and push out power structures to the in-between spaces, to the walls of each bubble that makes up and facilitates foam. Brekke adeptly outlines this situation:

What often gets forgotten in the meantime is that once you get rid of an institution, which in this instance is the bank, you actually have a radical reintermediation that takes place at the same time. You literally have new media that come in the sense of cryptography, code, developers, fibre optics, so on and so forth… It’s kind of a replacement of the traditional institutional format with a whole new set of actors and players, including non-human actors and players, that actually operate in entirely new ways. What that means in terms of power, in terms of accountability and decision making, is for me a very interesting and quite a daunting thing, but a very important thing to try and understand if we are going to shift some of the central institutions in our social and political life to a model that takes this type of form for reaching decisions or reaching agreements between people. We are creating a situation where software engineers are the legislative branch of this situation. They write the codes, they divide the systems’ (Haase and Brekke 2016)

Patainstitutional models that are described as open, participatory, distributed or networked, that are often bottom-up and that aim for inclusion, are clearly ripe for experimenting with to explore the potential for more resilient, more legitimate social spaces than those dominated by the traditional financial market. However, despite the rapid, seemingly spontaneous spread of this foaming space, there is a need to look closely, to understand and locate the re-mediation and redistribution of protocols that reside rather than in the centre, in the seemingly ‘lighter’ spaces of facilitation. Who rushes in to set these terms? The warning signs are there: old boundaries set by prejudice, power and wealth accumulation are still prevalent in these spaces whether the racism towards black users of Air BnB, the precarious working conditions of Uber, trolling on ‘distributed media’, the monopoly of Google in the ‘open’ space of the internet and the fact that major players in finance are currently driving much of Blockchain. Open can equally equate to hidden.

When we think of a ‘platform’, or the ambiguous term ‘open’, they seem post-political, somehow spontaneous and unmanaged, but social space is never neutral, there is no ‘natural’ Rousseauian way of being or unchartered space to return back to. The ‘thought-image’ of foam recalls this spatial situation. Although foam is lively and distributed, a plural, collective space, bubbles have the property of being open and closed at the same time, of being individuated yet also necessarily interconnected. This is a reminder that in any organisational structure whenever there is an inclusion, exclusion also takes place. Sloterdijk writes that:

Foam […] constitutes a paradoxical interior in which, from my position, the great majority of surrounding co-bubbles are simultaneously adjacent and inaccessible, both connected and removed […] This formulation is meant to block access as early as possible to the fantasy that was used by traditional groups to supply an imaginary interpretation of being: the notion that the social field is an organic totality integrated into a universally shared, universally inclusive hypersphere (Sloterdijk 2016, 54).

As well as the skillset of the designer, to navigate foam and craft cooperation, we need to be adept investigators and researchers, attentive and alert, able to trace hidden activity and interpret new ways of working and being in the world. We need to constantly be aware of who and what is being gathered in order to take which decisions. Power must not recede from view, but be made apparent, taking care to nurture governance and protocol is crucial so that organisational structures and ways of collectively coming together, of making decisions about the world, are in line with a diverse, teeming set of values.

Yield

Narrated by Marsha Bradfield

‘Yield’ is one of those curious words that denotes disparate values. It can mean to produce or provide a natural, agricultural product, as in the ‘yield of a field’. But it can also mean to surrender, submit, concede: ‘yield to traffic with the right of way’. Mixing metaphors, I want to reflect on Critical Practice as a vehicle for open knowledge production that yields in both senses, making the term doubly metonymic, a bumper crop. Following the logic of ‘jig’ as a ‘relational machine’ and ‘foam’ as a ‘thought-image’, ‘yield’ is proposed here polysemically to help us to better grasp the production of Critical Practice as a patainstiution.

Flyer, currencies and programme, some of the souvenirs from #TransActing; a market of values, July 2015

The particulars of patainstiutionalism I consider here are indebted to Mick Wilson’s thinking on parainsitutionalism. This he deftly tracks through withdrawal, refusal, escape and other manoeuvers in contemporary culture that is produced in/through/for institutions and further organisational structures (Wilson 2015). In a 2016 lecture at the ICA (London), Wilson used institutional critique to frame these parainstiutional manoeuvres as what he calls ‘bourgeois revolt’. Though not something he advocates, Wilson appreciates its appeal. My sense is that Critical Practice would feel similarly and regard the parainstitutionalism of Bourgeois revolt as something to understand and refigure en route to creating other, more socially-produced modes of opposition, ones that involve collectivising to constructively oppose the logics of capital (Wilson 2016). In this way we can differentiate the two forms. The ‘para’ in parainstitutionalism denotes not only ‘beside’, viz. paramilitary, but also connotes ‘using and abusing’, as in parasites. By contrast, we can think of the ‘pata’ of patainstiutionalism in terms of a different emphasis, one perhaps defined less by interdependence and more by alterity: patainstutitions are ‘other’ to and often actively othered by institutions. What this means in practice will likely become more clear in the discussion that follows, as I kick against Wilson’s description to explain why the extractive manoeuvres of bourgeois revolt are broadly anathema to the practical and philosophical approach of Critical Practice and hence its patainstiutional yield. This makes Wilson’s thinking an unlikely but also potentially fruitful way into my metonym of choice.

Instead of giving (i.e. yield as in distributing excess or giving right of way), bourgeois revolt is about taking. This begins with institutions taking advantage of those who I will hesitantly call their subjects (faculty members and staff but also students in the case of institutions of further, higher and other education). More important than what these people are termed here, or the type of work they are expected by institutions to do, is how the experience of these subjects makes them feel and what consequences this has for their quality of life, both as a singularity and an expression of the common. Many of us experience the process of ‘being institutionalised’ as tantamount to ‘being taken’ or captured. Hence why this is the catalyst in Wilson’s description of bourgeois revolt: we feel exploited, yes, but in time, some also feel rebellious. This drive is proving tricky everywhere but, perhaps especially in the socio-politico-economic contexts of the Global North, replete with their creaking institutions and other infrastructures that once served the public good in the name of rational liberal democracy. Cued by Wilson’s thinking, we could say that bourgeois revolt depends on reciprocal extraction: ‘One takes an institutional role, one takes resources—access—[visibility] but […] one produces a work world identity or subject position for oneself that is predicated on a rejection of the institution in part or in whole’ (Wilson 2016). As this description of bourgeois revolt makes clear, this relation is often parasitic. Subjects find meaning through subterfuge and sabotage, extractions like siphoning off resources and prestige not only for their benefit but, crucially, at their institutions’ expense (Wilson 2016).

There may be formal similarities between this parainstiutionalism and Critical Practice’s relation to Chelsea College of Arts. For starters, the cluster has benefitted from institutional support: occasional funding, some space to meet, a bit of storage, intermittent administration and publicity, but most of all research time and the art school’s learning environment. These things, however, are given as resources to Critical Practice in exchange for and in support of its work and contribution. In turn, the cluster’s long-term but also largely independent guesting at the college garners the latter credibility as a progressive institution in certain worlds of critical cultural production.

How does Critical Practice perform parainstiutional rebellion? The short answer: it doesn’t. In my twelve years as a member, reciprocal extractions from either the cluster or the college like the kind described above have been few and far between, always a last resort and never emotionally satisfying. There is a lot to unpick here. I would not like to valorise the cluster’s practice as morally superior any more than I would like to suggest that everything is copacetic with the college’s own instituting. Neither college nor cluster is beyond critique. Rather, my immediate reason for highlighting the non-participation of Critical Practice in bourgeois revolt is to make a simple but important point. Instituting through behaviours of extraction may be increasingly pervasive, born of the desperation that so many of us feel in these uncertain times. But surely this does not mean that the best we can hope for is a bad relationship with/as our institutions. If Critical Practice is any indication, less mutually toxic forms of insitutionalism are also possible, though admittedly tough to achieve. Operating in good faith for more than a decade has resulted in circumspect reciprocity between cluster and college. And yet, this symbiosis cannot be taken for granted, even after all this time. Though easier said than done, especially at times to austerity, institutional or other support ought not to be sought and accepted without considering both the short and long-term consequences of its unstated expectations and the asymmetrical relations that will result.

To grapple with nuance like this, the stuff that attends exchange, Critical Practice has looked to the sociological insights of Marcel Mauss, especially his work on the potlatch and it’s gifting as a complex and contingent way of circulating value (1966). There is a good reason why this circulation preoccupies Critical Practice. The cluster’s economy trades on enthusiasm and peer-to-peer (or P2P in tech parlance) exchange. When budgets are miniscule, the challenges of who is paid, and who is not, who can afford to work for free and who cannot and how these realities are negotiated and remunerated through non-monetary forms of payment remains an evergreen concern. Grasping the mixed economy of paid, badly paid, unpaid, volunteer, self-subsidised and peer-to-peer subsidised work involves understanding the social and further forms of reproduction that unfold through gifting, guesting, hosting and other informal and non-monetised exchange. This was central to #TransActing: A Market of Values, its content and form, with both aspects aspiring to ‘value values that are not usually valued’ (the project’s motto). These include social values like trust, care, appreciation, loyalty and mutual support. So when it comes to the instituting of Critical Practice, it would be more than a mistake to assume this is sustained through the behaviours of bourgeois revolt. This undermines not only the cluster’s ethos of generosity but also its commitment to open, transparent and accountable self-organisation.

One of the best places to look for evidence of these things is on the Critical Practice wiki. It is a dedicated digital space for self-organising the cluster’s economies and ecologies of collaborative cultural production. I want to think about this yield not only in terms of what is produced but especially how this takes place.

Criticalpracticechelsea.org is a growing yield of diverse crops: meeting agendas and minutes; records of self-governance, including open budgets; research reflections, reports, evaluations, documentation and discussion of #TransActing and other projects. I am fond of likening this site, which uses MediaWiki (the same software as Wikipedia), to a communal garden. This is the meaning of yield that regardless of value connotes fertility, fecundity: abundance. Or, to borrow a turn of phrase from Actor Network Theory (A-N-T), the wiki is a ‘network of heterogeneous materials’ (Law 1992). There is plenty of evidence all over the wiki of the cluster’s bountiful knowledge production, which we have come to better understand and appreciate, thanks in part to the insights of A-N theorists. John Law, for instance, prompts us to recognise the wiki as a product or network effect of Critical Practice as the cluster uses this online platform to order and reorder traces of its activity in the service of its needs and aspirations (Law 1992, 380).

Criticalpracticechelsea.org is populated with concrete expressions of the Market’s planning: records, lists, schedules, drawings, photographs and the like. These are organised into a patterned network that overcomes the boundaries between digital documents with hyperlinks connecting the wiki’s pages. It is radical to understand this yield as part and parcel of the Market because this means it was transacted through exchange that meaningfully outstrips the spatiotemporal experience of the event on a sunny day back in the summer of 2015. This is also radical claim because it regards the Market as a network of heterogeneous materials that extends all the way into the very journal you are now reading via this account as a durable trace of some of #TransActing’s bountiful yield. So the argument is that the cultural field is so much more than a collection of artworks, plays, pieces of music and similar aesthetic expressions. These creations are necessarily dependent on the heterogeneous materials in their networks, including institutions that, through instituting, generate effects such as organisation. Or, in the case of Critical Practice, the self-organisation entailed in patainstiuting.

In arecent paper I explore this more thoroughly via Gerald Raunig’s hugely influential proposal of ‘instituent practices’ (Bradfield 2020). In this other discussion, I pitch Critical Practice’s pata/para:instituting (more verbs than nouns) as constitutive activities that are mutually energised through dialogic exchange. Simply put: no wiki, no cluster—or at least its particular approach to self-organising would be much more difficult for reasons that should soon become clear. Although Raunig foregoes an explicit definition of instituent practices, their value tracks with their emancipatory potential (Raunig 2009). More specifically, this comes from these practices as they puncture the narratives of limit and enclosure that seem to predominate so much critical cultural production. Raunig gives the example of Andrea Fraser’s defeatist statement of institutional critique: ‘We are trapped in our field’ (2005 as quoted by Raunig 2009, 5). What other more empowering stories can we tell ourselves regarding our places/sites/contexts/platforms of practice? How might other narratives prime us for activity that is more liberated and potentially liberating in its experiments with alternative ways of instituting? Earlier I spoke about bourgeois revolt as a parasitic response to institutional capture. Wilson’s sense of this draws on that of Raunig, with both proposing alternatives to the conservative image of flight as withdrawal, ‘the individual turning away from society’(Raunig 2009, 8). What they instead advocate is a self-critical relation that is non-escapist but also, and crucially, open—open in ways that move beyond its own being-institution and all this entails (Raunig 2009; Wilson 2016). With this in mind, I will link the cluster’s long-standing commitment to openness with the meaning of yield as in ‘giving way’.

Soon after Critical Practice was established in 2005, it adopted the principles of the open organisation movement (P2P Foundation 2006). These include ‘open’ as in ‘open source’ (the code is non-proprietary; the cluster’s tools of self-organisation, including the wiki, are placed in the public domain). The cluster also aspires to be ‘open’ as in ‘open access’ (in theory, anyone can join; in practice, those who live in London have a clear advantage, for example). Further, Critical Practice is also explicitly open to new experience (the cluster actively seeks feedback through collaborative cultural experiments like the Market). The cluster’s commitment to openness in its various forms explains why Critical Practice’s very own compact of self-governance is literally open, or under erasure. Published on the wiki, the ‘Aims and Objectives’ (Critical Practice 2017) can be edited in the same spirit as Wikipedia, in response to new information, understanding and experience; though in practice, the cluster’s formative documents have remained largely unchanged for more than a decade. The wiki is radically open to the extent that anyone with internet access and a readily-available-but-spam-preventing password can use and abuse it—and the latter sometimes happens. The wiki has been the target of several devastating hacks. It goes without saying that openness comes with risk.

How much risk and what type depends in part on the ways in which something is open. In the wiki’s case, its open access is matched with editorial transparency. Every saved change is archived and attributed to the user who makes it. This occurs on the History pages. While operative ‘behind the scenes’, anyone can click on a link that gives them access to this historical record. But on the surface, the wiki’s Read pages automatically present content as unattributed. In other words, there is no way to know on these pages who authored what or who the text pertains to, unless this is explicitly stated. ‘So-and-so expressed such-and-such’ only appears if someone has literally typed and saved this utterance. Sometimes we do, when, for instance, taking meeting minutes. These often include a list of action points along with the names of those who have agreed to take responsibility for their completion and, like the cluster’s agendas, budgets and other planning materials, the meeting minutes are both edited and archived on the wiki, making them available for public access and scrutiny. Moving online and offline, this accountability provides feedback loops that help to make Critical Practice a self-regulating system.

It does not take much to appreciate why the kind of subterfuge and sabotage discussed above with reference to bourgeois revolt would be difficult if not impossible to perform on the wiki. Every input can be attributed to its user and with few exceptions, their real-world identities are known because we work together, face-to-face. It could, of course, be argued that this P2P architecture is oppressive, its transparency operating in the service of the audit culture and surveillance capitalism (Rosamond 2018). There may be some truth to this. For sure, criticalpracticechelsea.org and the wiki before it were established at a time of greater techno-utopianism. Here again the metonym of yield as in ‘to give way’ is useful, reminding us that even our most cherished beliefs are subject to challenge and change.

A bounty of aesthetic, ideological and informational traces, the wiki will remain both a community and a public resource. That is, as long as the server fees are paid, the domain name is renewed, occasional maintenance is undertaken and spam is weeded out. All things being equal, which they rarely are, criticalpracticechelsea.org will fulfil Aim 5 of the cluster’s compact of self-governance ad infinitum: ‘We will return publicly-funded research to the public domain’ (Critical Practice 2017).

I have considered two meanings of the word ‘yield’ to probe some of the particularities of Critical Practice and it patainstitutionalism. While only scratching the surface, this probing has coaxed into view something vital. Critical Practice not only takes seriously its own becoming institution through specific modes of self-organisation, it does so without succumbing to a pair of common pitfalls: either fixating on self-obsessed theoretical critique as an alibi for its own institutional involvement, or engaging in toxic and self-demeaning snipes at its institutional host or the cluster itself like those characterising bourgeois revolt. The cluster’s licence to operate springs instead from how, through practice, it critiques its own form. This is crystalised in its Aims and Objectives: ‘We will reflect critically upon, and act creatively within the contexts in which we operate - including the very conditions of our own possibility’ (Critical Practice 2017).

Birdseye view of #TransActing; a market of values, July 2015