Issues- Journal Press- Contact- Home-

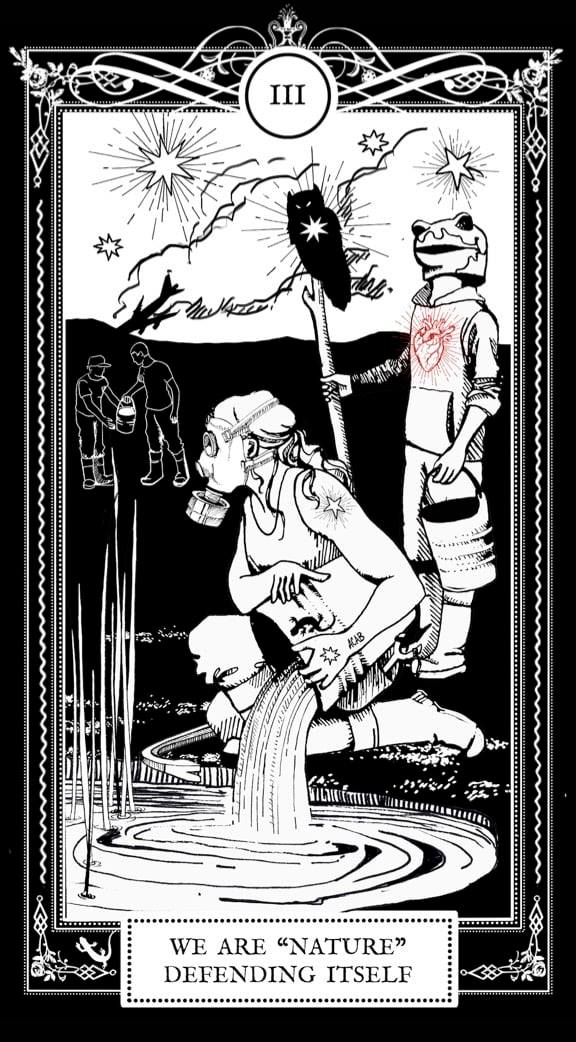

A Forward to Isa Fremeaux and Jay Jordan's We Are *Nature* Defending Itself

(Purchase the book through Vagabonds/Pluto Press)

Marc Herbst

The entangled and extended autonomous rebel community that comprise the zad, located near the village of Notres-Dame-des-Landes in Britany, kicked the French state’s ass.

Over the span of 6 years they scared off the cops and their courts, and ruined some dumb multinational’s plans for stupid stuff. There was a time when the heart of this book would simply be a discussion of how the state was forced to come to terms with these rads so that instead of an airport, their squatted homes and farms were allowed to stay.

But, as the reader knows, large and actually meaningful insurrectionary movements are heterogenous beasts. And our authors, Isa and Jay of the Laboratory of Insurrectionary Imagination (LABOFII), would be the first to say that there are a million ways to tell its story. So We Are *Nature* Defending Itself is their story, an ecofeminist book showing how attention to ritual, art and actually existing relations are more than theoretical; the combination of these things are constitutive of their radical success. These things constitute an art that aims towards constructing other livable futures.

Magic happens, bitches.

The zad; a play on a French government acronym, meaning a zone to defend.

4000 acres of wetland

The dumb idea: building an airport NO ONE NEEDS

Salamanders and tractors

A good idea: “to defend a territory, you need to inhabit it”’

70 squats, over 300 rebel residents

6 years (pretty much) without the state

Cows and barricades

40,000 people occasionally appear to put a halt to the dumb plans

Cheesemongers, a sawmill, radio station, flour mill and more

Teargas, concussion grenades, rubber bullets and worse

Tanks and wounds

Songs and ritual

The airport will never be built

A Revenge against the commons

frogs

It is now May 2021, though a manuscript of this book had been delivered to me at the beginning of 2016. At that point it was a nearly complete blow-by-blow of the zad's struggle. The book was meant as a call-to-arms for the English-speaking world, to be published by the Journal of Aesthetics & Protest, which I co-edit. I was in England then, and at the time it seemed that only those young queer punks who travelled to and from the continent and a cool guy at the anarchist bookshop really knew what this zad thing was... even though public awareness and excitement would increase whenever dramatic struggles on the territory became front page news.

Nodding off while reading the draft of the early manuscript, I read the scene of a village being constructed with thousands of hands passing materials; boards, windows, hammers, drum-kits, radios, through the night into the forest: a vision of collective struggle. The next day I woke up thinking I had dreamed this section, but I had read it, it was real.

Enchanted, I asked the authors for more details on the wetlands and hedgerows, and on the different factions involved in organizing the deep and extended solidarity. Eager to go to press, the book’s deadline somehow nevertheless kept on being pushed back... the people of the zad kept winning. It became apparent that we wouldn’t be publishing a call to arms for a battle yet to come, but rather something else, a reflection on victories. The authors’ early drafts had an argument about integrating art into life, which confounded me. In the same way that the picture of the landscape of the zad’s unusual bocage landscape challenged my imagination I also couldn’t see how the question of art mattered in this radical land full of fresh air, so far from any museum.

Before they moved to the zad and became land-defenders I had came to know the authors, Jay and Isa, as city creatures: high-achieving university-trained individuals who’d excelled in the critical and radical spaces carved from arts and academia. I initially read their critical attention to art in the early drafts of this book as a hold-over from their concerns that time. As an editor with a long engagement with activist art and theory, I knew them as activist saints whose creative activities impacted countless movements. As individuals and together as LABOFII, they’d applied their skills to a variety of problems; in the 1990s Jay had collaborated in founding Reclaim the Streets that made a wild party of highly disruptive protest; which besides ACT-UP is, by my estimation, instrumental in the revival of a popular post-cold-war left. While British-born Jay came to his activities as an artist, French-born Isa arrived in the UK as an academic interested in popular education. Within the context of an urban activist's life they applied their intelligence to LABOFII, a popular education and collaborative arts platform that runs not projects but mobile, exploratory and participatory experiments in rebellion, finding ways to weave together arts funding and popular movements to catalyze carnivalesque resistance, for instance at G8 and UN Climate Summits, using clowning, gaming and bikes.

In those years, when I was living in Los Angeles, I visited the authors in London at the height of the Climate Camp movement. In their flat, I shared my observation of how wildly popular London's green movement seemed– what with all these protest posters in the city's hippest neighborhoods. Nodding in agreement, there was a comment about how young society darlings were on the radio speaking up for climate resistance. Upon my return to London several years later, it was sad to recognize just how fleeting that idealism and attention was, how quickly those posters came down.

As is detailed in this book's pages, it was these sort of things that drove the author’s desertion of the city and the episodic sensibility of activism, art and academic culture and drew them to the zad, where a very different way for art, study, struggle and life in common was possible.

Neoliberalism promises civil society that lives will be peacefully played out as a game, on a field whose reliable rules are apparent for those who learn well, and whose rules are the tools to game the system in order to peacefully live. Or better, this is the convoluted promise it makes to its privileged subjects. Neoliberalism declares itself the end of history. It's peace is promised by its allowance for variation upon a fixed field. Under these terms, art all too often resolves itself into either a method to propagandize either the singular artist’s genius or a method to ethically change the field of play and the rules of the game. Under these terms, art may be nothing but then the moral kindergarten of capitalism’s neoliberal vampires– a place to signal “You want some enlightenment consciousness? Go look to art.”

In contrast to an art that plays moral games with the powerful, the zad was playing its own game and acting so that French state could not but recognize their autonomy. For this reason I thought, at first, that it was the zad’s culture that mattered in a way that needn't be defined by artistic dimensions. Its culture attended to questions of remedying imbalance, cultivating entanglement and mirroring a sensibility informed by Donna Haraway and Starhawk. With so much goodness at play, why pray to the gods of art?

The magic of the zad is its impossible but actual victory. This book shows us how this victory stems from attention to zones' birds, frogs and from the mundane day-to-day ways its people organized to live there, mediated through ritual and deliberation. These things were as much a vital part of the diversity of tactics that allowed the zone to defend itself as the dramatic and combative forms of solidarity that had made headlines.

At an editorial meeting in a bar on the street once home to London’s newspaper industry (but now just another place for overpriced flats), Jay explained a new vision for the book. Drying off from the rain that had chased us inside, he excitedly told me about biologist and philosopher Andreas Weber’s work: “nature is not a meaning-free or neutral realm, but is rather a source of existential meaning that is continuously produced by relations between individuals, producing an unfolding history of freedom.”

My raincoat was soaked through and wasn't sure if I was reaching some epiphany or if I was just happy to be warm. I poured back a response: this attention to scientific knowledge reminded me of decolonial scholar Sylvia Wynter’s focus on civilizational regimes of knowledge. For Wynter, the West’s ever-more reductionist scientistic knowledge system has increasingly fixated on what she calls “Man 2” or homo oeconomicus, one that is incapable of recognizing any meaning other than what can be personally gathered as purchases or personal accumulations.

Just because winners get to write authoritative history, we should never assume that other ways of living, being and understanding have evaporated. Insurrectionary imagination springs from somewhere. The textures of the Black, Brown, Indigenous, queer and feminist, entangled and anarchist and weird lives we lead constitute a rich set of values, ideals and practices for meaningful and complex beautiful forms of existence. The marginalized are so defined because their stories don’t officially count, not because they don’t exist.

When drafting a timeline of radical otherness' continuity in the shadows of the man and his guns and money, so much floods in that it reveals the conceptual limits of cultural hegemony. ‘We truly are the granddaughters of the witches you weren’t able to burn’. Cultural practices, knowledges and perspectives remain entangled within lives that would otherwise simply seem subject to capitalism's world-ordering. Relational threads are entangled within the everyday of common being, properly invoking the tangles and knots is the recipe for radical transformation.

In this context, the inspiration provided by the Zapatistas’ intergalactic communiques cannot go unmentioned. They demonstrated that other histories were never annihilated, only hidden from the world. But now, more than 25 years after their inspiring uprising in Chiapas, we are witnessing a subtle generational shift on the wild, more queer and communitarian side of the anarchist left. The spirituality of Starhawk, horizontalism, and the carnivalesque urban politics of Chris Carlsson are being supplemented by the more heterogenous, socially embedded and also systemically political ideas like adrienne marie brown’s emergent strategy, Dean Spade’s approach to mutual aid and the Care Collective’s focus on the communalization of reproductive labour.

This generational/perspectival shift in radical knowledge, community and praxis occurs as capitalism and its world-ordering collaboration with the most regressive of spirits manifest its knowledge that climate change heralds possible ends of worlds– its worlds. So beside this apocalyptic vision, the social knowledges and practices of those whose worlds already ended or were never properly allowed to begin, emerge as capable of reflecting what we have always-already known. Like the emergent anarchist cantons of Rojava, one thing that this book demonstrates is how eco-feminism is a consequential politics. The struggle of the zad also recalls the movement against the Dakota Access Pipeline (NoDAPL) led by the Standing Rock Sioux of the territories currently known as North and South Dakota. But where both struggles thrive on complex entanglements and solidarities, the zad is an experience of coming into a territory, rather than reconstituting intertribal and intercultural resistance and negotiating sovereignty.

Just because winners get to write history, we should never assume that assholes’ victories are final. As we imagine civilizational shifts away from the governing West’s total disregard for life, this book helps us begin to imagine other ways to orient entangled existence. LABOFII’s shift from piecemeal protest-based engagements to an open but situated practice is illuminating for all communities in struggle. The way one situates and orients one’s practice matters. It is noteworthy that, through the zad, LABOFII has been able to describe actual struggle and the generative life-ways it established with a horizon an inch-removed from capital’s climate fart. And in this, the book’s focus on art is not incidental.

Art historian and biopolitics scholar Josephine Berry writes in conversation of art as "a conspiracy of reason”. To take art seriously is to suggest that humans can, via emotion or intellect, move toward the right path. That art is a “conspiracy of reason” means that art’s affective powers can so overwhelm that art's speculative ideas and practices become widespread social practices. base assumptions and accepted facts of how life is lived. By calling their work “art,” LABOFII insists that their work matters for the fate of this thing we call civilization. As Weber and Wynter tell us, in different ways, societies orient themselves by the stories they tell themself. In that territory for living that they've made between their zad victory and the studied attention to mundane reproductive practices is an artistic frame through which their art matters for all our sake.

The authors focus our aesthetic attention on how entanglements can facilitate and constitute political transformation, and they have done the experiments to prove it in Brittany. So, for the sake of art and its conspiracy, this is notable. For arts’ sake, I have sought myths to frame the zad’s transformational collective art work: the camel passing through the eye of a needle, Persephone’s annual passage from the underworld to ours, the transition of characters in the Mayan Popul Vuh. Instead of landing on a single metaphor, I realize that what the LABOFII has done here is describe a sensibility to recognize and utilized the portal– the transformational portal.

Ours is an era of compounded crisis; one finds grace for art in its attention to the quality and sensibility of institutions that constituted this juncture. In North America, the New York-based activist consortium Decolonize This Place insistently reveals the thoroughly white supremacist nature of museums and the everyday by pairing popular abolitionist street politics with art’s tactics of institutional critique.They have joined others like the UK’s Liberate Tate in targeting statuses, monuments and art institutions and seeking to drive the forces of corporate greed out of the civic temples for cultural dreaming.

In collaboration with the Lummi Nation indigenous to the Northwest coast of what is currently the United States, the art-activism platform Natural History Museum have highlighted that institutional critique is not the only method for responding to the art world’s complicities; one can also reconvene with the land and its relationships. In Europe, LABOFII has also been pivotal in showing us the potential of a synchrony between grounded, land-based subjectivity and radical practice and in this book they articulate a radical sensibility built on the going beyond making singular, tactical interventions and, instead, recreating day-to-day life.

Our era’s crisis are based on the fact that there are so many moving parts to the problem. But, equally, there are so many moving parts for making our way through it. It can seem that so little has fallen into place. As art, LABOFII synthesizes so much into place. Militantly so, they are in constellation with culturally oriented feminist economics projects like Precarious Workers Brigade and Cassie Thornton’s efforts to respond to the biopolitical failures of Western governmentality. Equally, LABOFII vibrate with the affective tuning signalled by Pauline Oliveros and Ligia Clark, and with the many Indigenous, Black and Brown, decolonial witchy, queer and trans knowledge-cultivating practices currently swirling around in our times. Their practice contains so much because the day is long and life has many aspects.

Magic happens. Change happens. Between the many moving parts, LABOFII suggests one of many artistic sensibilities for finding a way to the other side, helping us navigate massive civilizational challenges and our being trapped in a history written by butchers. But the witches they failed to kill have already faced the ends of their worlds and lived to tell it. And, as Octavia Butler tells us, god is Change.

The cosmopolitical, the radical and the radically queer is entangled throughout the rich sociality of all life and its relations. To properly rebalance those entanglements towards something transformative and sustaining is an art and a work for our day. Recognizing that LABOFII has shown us this is possible, The Journal of Aesthetics & Protest has maintained a deep interested in co-publishing this book over the years. In that effort I'd like to thank Sam Gould for early publishing collaboration, Stevphen Shukaitis for his speculative writing related to the project, Amber Hickey for her strategizing, Jonas Staal for supporting some of the project research and Steve Lyon for his late help, Jay and Isa for so much, and Max Haiven for his collaborative editorial efforts.