Reframing the value of art and fair labor in the context of a sharing economy

By Natalia Ivanova Mount

-Natalia Ivanova Mount is a cultural activist, organizer and producer with extensive experience in nonprofit leadership. She is currently the director of Pro Arts Gallery & Commons in Oakland California.

(download pdf here)

The economics of art are active within a capitalist market system hence, it is only natural that they suffer the same consequences as other failing economic models that: 1) operate on the basis of perpetual scarcity in order to create monopolies; 2) assure profits are held by the “1%” of the population through privileged market access, tax laws, and systemic racism; 3) homogenize and commodify culture, turning a producer society into a consumer society.

Fragmented efforts to resuscitate a broken art market system have yielded a multitude of brilliant research and production in both the field of cultural theory and art theory. Unsurprisingly, most of this work remains largely closed off to those who work outside of the walls of academia, partly through its somewhat obtuse character and partly through the very limited level of distribution, such work can attain. This brings up important questions related to who exactly can participate – the value of the productions of cultural theory and art theory may only be accessed by those with a very specialized education. Most recently, there has been a concerted effort to open systematic structures to include unrepresented voices and marginalized communities within the context of the art institution. Yet, how can we talk about equity in the arts if we don’t address the underlying structures of fair labor, intrinsically connected to the value we attribute to art and art production? How can we implement a new system when those with real power continue to propagate a system that is based in competition, scarcity and individualism that primarily benefits them?

Mirroring the market system, the art market represents a network of direct market players, suppliers, and entities that influence the business environment. Not only do art buyers, sellers, professionals, and institutions control the production and exposure (exhibition) of new art, entering the art market but they also control the value of this art. In this market system, the value of a ‘new’ contemporary artwork is calculated through a formula: the time spent making the work; the cost of materials and labor; the size of the work; the medium; the artist’s education; the reputation of the artist; the market price for similar works; the career point in which the work was made; and the scarcity of production. This artificial value of the work is then tested on the international art market through travelling exhibitions and projects. Important to note here is that the reputations of hosting cities and institutions are intrinsically important for the creation of the international value (provenance) of the work. They can make it or break it. The last step in this process is connecting and converting logic of the perceived value of a work – established through the steps outlined above – to the logic of the monetary exchange of commodities in the art world, or system. When the work enters the secondary market, even when the dollar value of exchange does surpass all expectations at auctions, the artist, by this point, having no royalty laws to protect their production, is out of the profit margin equation.

The artificial measurements used in the valuation of artworks are created within the same capitalist market system that such a value refers to. Similarly, when deciding on how to value the labor of art professionals, an important part of this valuation includes the particular demographic of art professionals-the higher the position one occupies within the hierarchy of the art market system, the more likely one is to be financially privileged. If the art professional has a somewhat specific socio-economic status, wealth becomes externalized through associated institutional endorsement, through external institutions such as education and award-conferring bodies. Such individuals are, obviously, those most likely to be recruited to work at an established, internationally renowned institution. This is one of the mechanisms through which the market reproduces itself, and accordingly, establishes a lower tier environment of art organizations. The large institutions ironically depend upon the existence of a mass of small organizations to provide themselves with contrast. Therefore, large institutions are still perceived (by both the general public and those with specialized interest) to hold a superior value in our society than say, an independent art space dealing with experimentation[1].

Hence, the compensatory value of art labor and production is directly linked to the social value of the institution, within the local and international art market system, the public and the philanthropic arena. It is worth mentioning here that generally, art professionals’ labor[2] is still valued at a lower rate than their counterparts’ labor – professionals, who work in fields like technology, finance, law and medicine. This fact makes irrelevant the fact that most art professionals are in fact as or more highly educated and experienced in their field, as their external counterparts, who work in the fields listed above.

In his 2002 essay “HEART OF DARKNESS: A Journey into the Dark Matter of the Art World”, Gregory Sholette very succinctly analogizes the scientific definition of ‘dark matter’[3] to the composition of the population of the art world. The art world’s ‘dark matter’ in this comparison are the marginalized artists, essential to the survival of the mainstream, big art business. Extending this idea further, the ‘dark matter’ of the cultural industry are those marginalized art professionals, who operate within the independent art scene, and through their invisible, and usually low-wage labor, perpetuate a market system that primarily serves the 1% of the art world, whose power is able to perpetuate it.

Why is value important to discuss in the context of art, art labor and production?

When funding mechanisms break, individuals and organizations begin to depend on mutual production, cooperation, reciprocity and collaboration. Since the value of art within the context of the traditional art market system is directly linked to labor and capital, we need to create an alternative to the system that recognizes broader value contributions. We can start by replacing the ‘direct market players’ (producers, buyers, consumers) with ‘art commoners’ (art professionals, funders, and the public). The art commoners are engaged in the co-production of value, social and public goods, and the replication of local and global material and immaterial art and culture commons.

Secondly, we can replace the ‘suppliers’ from the traditional market system with ‘artists,’ who will mutualize their labor and production, co-creating new relationships with their peers and the public, and thereby dispersing the power associated with their skill, knowledge, experience and position in the art world, in the name of empowering others.

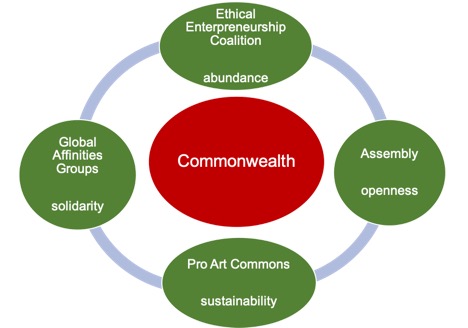

Lastly, we will replace the ‘entities that influence the business environment’ (government, infrastructure providers, industry associations) with a body that we refer to as the ‘Ethical Entrepreneurship Coalition.’ This body will invest in the infrastructure and sustainable growth of a sharing art economy; the just and fair distribution of profit and rewards; and the mobilization of social capital and community. Global affinity groups will contribute in the co-creation of an international commons-centric art world, which operates parallel yet autonomously to the official, International art market.

If we are creating a new art market system, then it follows that we will reconsider what constitutes fair labor and value of art in a commons-centric art economy. We will create an alternative currency[4] that builds community, social capital, and solidarity among partnering organizations, including public/private partnerships.

It is important to note here that we are not naïvely claiming that we will ultimately change the capitalist art market system per se but rather that we will attempt to expand the art practice and production that serve it, in the name of the common good. Rather than extracting labor and resources from our communities through capitalist-based art practice and production, only reproducing an industrial complex that imprisons art within an exploitative system, we will create art and culture commons, thus multiplying the labor force that is intrinsically connected to a value that can only emerge through the collective power to affect change. This strategy has the potential to eventually weaken the capitalist structures of the art market system, at which point a reconfiguration can liberate cultural workers from an oppressive continuum, perpetuated through an unjust system. We can only hope that our strategy works.

The Crisis in Value Extends to a Crisis in the Infrastructure of Independent Art Spaces

Along with the crisis in the perceived value of art, labor, and production, there is also a crisis in how we, as a society, value independent art spaces and their contributions to the commonwealth. The economic power of the independent art scene has been continually eroded over the past 20 years, due to the lack of investment in the infrastructure in it. As a result, the whole art eco-system has become dangerously unbalanced today. Those who create and participate in the independent art scene are continually under increasing pressure to find the funds to hold or secure spaces for art[5] and make a living, often through working in the mode of ‘self-exploitation’ in the system. Because of the difficulty in finding support for non-programmatic needs, such as administrative overhead, those operating independent art spaces are divorced from their ability to bring any change to their field. Independent spaces are kept within a certain boundary of activity, and are simply rendered impotent through the control of the funders. Hence, those spaces, and by extension the art professionals working for them, remain complicit in perpetuating its hierarchies and institutional hegemony. Voluntarily joining the ranks of the ‘working poor,’ these art market players’ only hope is that one day, this system too, will crash. Instead of continuing to apply band-aides to a broken art market system, I propose we co-create a new one.

Sustainability >> Openness >> Solidarity

*Proposed investment model for Pro Art Commons: ¼ artists, ¼ public, ¼ cultural workers, and ¼ funders.

Pro Art Commons

Sustainabilitiy

• Co-create shared material and immaterial resources and services.

• Co-create solidarity bonds with local and global commons and open co-ops.

• Co-produce art and programs.

• Earn living wages.

• Equally share assets, profit, income, expenses, and funding.

• Practice transparency in all operations through open co-op tools, such as: cobudget; loomio; optimi; and others.

• Co-create an alternative currency that has a circulation throughout Oakland (solidarity partnership with landlords, supermarkets, restaurants, cinemas, etc.)

• Practice reciprocity and cooperation in all operations.

• Empower other organizations with the tools to reframe their practice to a commons-centric model.

The Assembly

Openness

• Engage in the research and development of commons-centric models for art organizing, production, and exhibition.

• Engage with specific issues, emergent from Pro Art Commons such as: alternative, social currency; an alternative art market; the value of art and art labor in post-capitalism, etc.

• Co-organize international knowledge-sharing events, such as: symposiums; reading groups; think tanks; working groups; articles; books; pamphlets; zines; forums, digital participatory platforms; and long-term projects.

• Co-create new strategies to mitigate traditional art market structures that are exploitative, countering them with an equitable set of economic relationships, such as: people before profit; fair labor; open participation in the arts, etc.

• Research, develop and pilot programs, such as UBI for artists and art professionals.

• Advocate for more infrastructural resources and funding for emergent art and culture commons and other open organizational models.

Global Affinity Groups

Solidarity

• Co-create a global network of commons-centered, affinity groups, which will engage in knowledge-sharing, mutualized art production, labor and exchange.

• Co-create an open fair license that artists and cultural workers use when contributing to the material and immaterial art commons.

• Co-produce the first decentralized, peer-to-peer, International art biennial.

• Co-create open-source digital platforms and networks for the co-creation and distribution of research and work that propels the idea of solidarity economy.

Ethical Entrepreneurship Coalition

Abundance

• Change art market and funding dynamics from a position of scarcity to a position of abundance.

• Work directly with City and State to turn these government bodies into enabling and empowering partners of an ethical art economy that is generative vis a vis the commons.

• Invest in the infrastructure and sustainable growth of an ethical art economy; the just and fair distribution of profit and rewards; and the mobilization of social capital and

• Collectivize risk, break competition and monopolies, and disrupt institutional hierarchies in the name of collective prosperity.

We can think here of how and what the “community of reference” means in reality; you and I may relate to a demand differently, its fulfillment may imply different changes to your life than it does to mine. A demand will mean something different to an unemployed Caucasian 20-year old male in Glasgow to a middle-aged Asian single-mother of two living in Bradford. Yet we can speak across these differences, as the common demand provides a connection and basis not for ‘sympathy’, but for solidarity – we want a demand to produce commonality across difference, not through the denial of difference.

Commonwealth

All circles will work towards the commonwealth of every part of our society. Supreme authority is vested in the people. All circles work towards an open, knowledge-based society.

All circles, previously fragmented, will connect and feed from each other, through a rhizomatic, circular structure, based in openness, knowledge-sharing, and fair labor practice and production.

Shared resources and services will create social value in our individual and collective production of art. Any surplus in the system will be re-invested in it, and equitable shared among all commoners and artists, part of it.

Footnotes

1. As experimentation in art has not been tested by the market, its ability to convert to any meaningful dollar value is unknown. It is tolerated precisely because it if from this pool of creativity that the market itself derives (future) content. Interestingly, there is no open futures market in art as of this writing.

(back)

2. ‘Professionals’ here obviously excepts those with any significant title within an art institution. Any position that requires a prefix such as ‘senior’; ‘director’; ‘chief’; ‘executive’ will receive a higher rate of compensation, at a rate of multiplication of and in reflection of the compensatory structures of the external professionals’ market. Those holding such positions are in a strict minority. (back)

3. The scientific explanation of “dark matter” describes the ‘matter’ that exists between the stars. This ‘dark matter’ accounts for approximately 85% of the matter in the universe, and about a quarter of its total energy density (back)

4. There are many examples of alternative/complimentary currencies: Culture Coin, developed by Howlround, a Center for Theater Commons; Ithaca HOURs; Canadian’s LETS; Christiania, the Free City of Copenhagen’s local coin, the “wage”; the BerkShare in Berkshire County, Massachusetts; “Fureai Kippu” in Japan; TOREKES in Ghent, Belgium; TIME BANKING in Blaengarw, Wales; The BONUS for emergency situations; BUS TOKEN in Curitiba, Brazil; AVL-Ville Money; etc.

(back)

5. Finding funding for programs (exhibitions, education, public programs) offered by independent art organizations is disproportionally weighted against those monies, available to satisfy the basic needs of such an organization: rent, utilities and employee salaries. Without the latter, the former cannot be brought into existence. Therefore, it is logical to conclude that there would be no independent exhibitions or other programs without the shadow labor of arts organizations.(back)