LOSING MY SELF:

Some anecdotes about anonymity

by Ian Milliss

If I subscribed to the notion that the measure of an artist was purely the degree of attention received from the conventional art world (broadly defined as the art institutions and art market and the artists that serve them) then I could claim the unlikely distinction of having been both a feted youthful prodigy and a late bloomer. For 35 years, between those two periods I became invisible, at least to the Australian art world, and I discovered the many different sorts and uses of anonymity.

Installation 1970 by Ian Milliss which rearranged gallery furniture

and partitions to create an enclosed seating area within the exhibition.

In the fairly small Australian art scene I was well known before I was out of my teens for work done in 1969-70 that was among the earliest and most publicised conceptual art, mostly involving the audience carrying out sets of instructions, often with interaction between audience members . The actions became less distinguishable from normal daily activities until they weren't even occurring in definable art situations, in fact they were simply interventions in normal daily life.

In 1971 everything changed. A local union, the New South Wales Builders Labourers Federation (BLF), at the request of local residents invented the green ban (a ban on demolition or building work in support of an of an environmrntal or heritage issue) to protect an area of harbour side bushland from development, the first of over fifty green bans. It struck me that the BLF's interventions were a larger scale version of what I was tentatively trying to do and therefore as a collaborative group they should be seen not just as artists but possibly the most effective artists in the world at that time. I was soon swept up into the most contentious and violent green ban of all when most of the residents were forcibly evicted from Victoria Street, Potts Point, a traditional artist's and worker's area where I lived. I became a founder of the residents group which retaliated by setting up a large squat to defend the street but was in turn subjected to bashings, kidnappings and ultimately a murder.

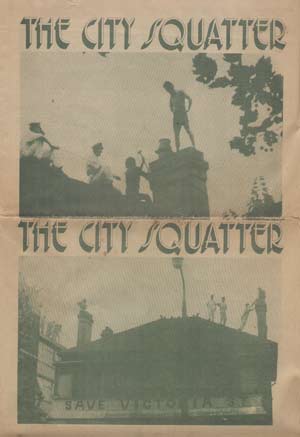

Ian Milliss was a founding member of the Victoria Street Resident

Action Group which in 1973 began the contemporay squatting

movement in Australia. The CitySquatter newspaper memorialised

their eviction from the Victoria Street properties in 1974.

It was then that I began to think seriously about anonymity. In 1971 I stopped exhibiting or trying to document my activities in a form palatable to the art world. I began to argue that the term artist only applied to those individuals or groups whose activities, regardless of their form, generated cultural change. While art world success required name recognition and ceaseless self promotion, I realised it was delusional to think that the art world as it stood created cultural change - it only created cultural fashions. I began to think that most who called themselves artists weren't, and most who were artists were anonymous because they never appeared in the art world. I came to see the art world as parasitic on the fundamental human activity of the continual process of cultural evolution and one way of combating the parasite was simple refusal to play while creating entirely different games outside of it.

The BLF members were undoubtedly generating massive cultural change. I felt that if the ability to generate cultural change was the real game then my art world identity was essentially meaningless. While I had discarded my delusion that artists were more creative than the average person I also realized that the BLF leadership were not only more creative than most artists but also more savvy about the media and culture. Slightly embarrassed, I realised I should just shut up, watch and learn. Consequently while using the skills and contacts available to an artist I never emphasised my history as an artist because it made the relationships simpler with fewer explanations. Although we ultimately lost the battle in early 1974 my world view was permanently changed.

This article by Ian Milliss from The City Squatter parodied art

reviews by reviewing the squat's various approaches to barricading.

Click the image to view a larger.

Despite my increasingly eccentric attitudes I remained on the art world A-list until 1976 when I became completely persona non grata (to the museums at least) for my role in organising demonstrations demanding 50% representation of both women and Australian artists in the newly formed Sydney Biennale. Unplugging the Prime Minister (a conservative who had risen to power in what was considered an unconstitutional coup) in the middle of his opening speech didn't help. Thus began my rapid slide into another form of anonymity, the anonymity of being shunned.

Not that I was concerned by that, it was in fact a matter of pride. My main activities were outside the art world – anti prison activism, for instance – or on the borderline such as organising community exhibitions on the effect of open cut coal mining or sustainable agriculture. This was the point, the late 70s, where the careers of my peers were taking off in the conventional sense. It was the time when the commercial conceptualesque began to proliferate as mass entertainment while those like me who had pursued conceptualism's radical potential found ourselves forced out of the mainstream.

Having discarded the idea of making works of art I, began to see my practice as the investigation of a range of different ways of being an artist or as Richard Dawkins would later put it, the innovation and adaptation of cultural memes. On the other hand I didn't see art or art works as meaningful categories except as a term for the various detritus that resulted from the real activity, the constant evolutionary process of cultural adaptation that proceeded through all sorts of media (in the McLuhanesque sense of the word) carried out by all sorts of individuals and groups. I was interested in applying myself to multiple outlets of cultural adaptation.

This was where I encountered a different anonymity, the invisibility brought about by the art world's belief that I was doing nothing because my activities were not seen as legitimate, did not produce marketable artefacts. I was regularly asked why had I given up art when I had such a promising future? When I explained that I had not stopped being an artist, that although I had discarded the very idea of art works as irrelevant I now had other audiences as well as the art world and worked collaboratively and in different media, I was always greeted with a puzzled, sometimes hostile, disbelief. For them, if it didn't happen in the art world it didn't happen.

When the Australian members of the recently disbanded New York Art & Language group (Ian Burn, Terry Smith and Nigel Lendon) returned to Australia in the late 1970s we teamed up. They provided me with desperately needed friends of broadly similar viewpoint, while I provided them with a way out of the A&L dead end through access to real political activism.

With many others we formed the Media Action Group in order to produce slide shows analysing the ideological biases of the mainstream media. Then in a tighter group we set up a business, Union Media Services Pty Ltd (UMS), to provide publishing and campaign services to trade unions and community groups. This was where my diminished art world identity became an advantage. There is no doubt that if we had approached the unions as a group of artists eager to get involved we would have been laughed out the door. Because I could approach them as someone with a known history of union involvement and a range of political and media skills, they listened. Later, when we had their confidence and used our connections to get them government arts funding to help develop campaigns they were slightly suspicious but decided they shouldn't look a gift horse in the mouth.

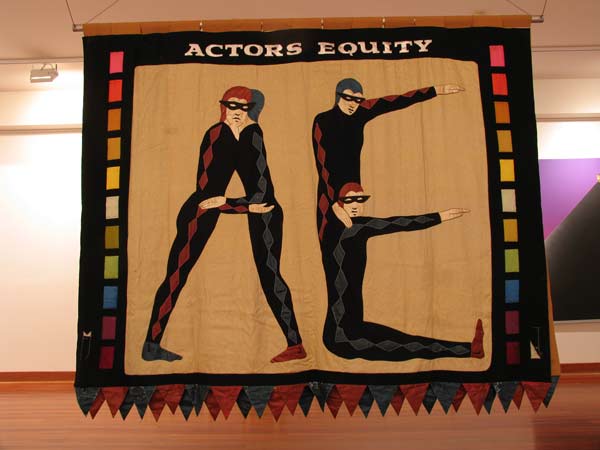

Ian Milliss managed the production of this two sided embroidered banner by Union Media Services Pty Ltd for Actors Equity in 1984.

Design by Michael Fitzjames, embroidery by Noela Taylor.

Within a few years UMS became influential in reforming trade union communications. While working for over fifty different unions, community groups and government departments, our example spawned a small industry of social marketing agencies that continues to this day. Australian trade unions are far more politically influential than their US equivalents so we were playing a critical role at the heart of political power. While this may be the dream of many activist artists the corollary was that the art world no longer regarded us as artists at all. By this stage in the mid 80s I did not care particularly, believing that eventually there would be some understanding of the significance of our activities but first we must push them as far as we could and leave the establishment of our art historical position until later.

On the other hand, Ian Burn spent considerable energy seeking art world publicity and validation of our work. Although we later split because of business problems, conflict over this was an aggravating element. For instance, our involvement in an Australia Council program supporting trade union arts activities came to dominate his time more than work for the unions themselves.Consequently, his art world reputation grew while his trade union influence diminished, all the while my art world reputation shrunk further as my trade union credibility grew. At the time of his death in 1993 he had little political influence but paradoxically was widely recognised in the art world for his political activities. Concurrently I held an influential position in the trade union movement specialising in media and cultural issues while the art world view was that I was no longer an artist.

This illustrates perfectly the conundrums of artistic identity, anonymity and political potential; that “political art” can rarely be more than ineffective posturing for a dilettante audience. If you are serious about creating political change then you must work with audiences outside the minute art world. While that risks your art world identity I feel it is a spurious identity in any case.

In recent years I have again been receiving art world attention. A recent article (about disappearance as a bad career move, of course) described me as the most baffling Australian artist, the poster boy of disappearance, indeed the only Australian artist whose reputation survived the career suicide of refusal to exhibit. This inscribes the final part of the cycle. I have played along partly out of ego (let's be brutally honest) but also because I think that it is necessary to illustrate to younger artists that things can be done differently. I have no problems with art institutions presenting history, including my own, even if I do have problems with their recent history of manufacturing contemporary art fashions. It may be that fashion has finally accepted my 40 year contention that the role of the artist is to generate cultural change rather than manufacturing for the trade in objets d'art, although I doubt it. I see even less sign that they accept the scarier proposition that the title artist can only be bestowed in retrospect on those who have demonstrably shifted the cultural memes. That would require accepting the likelihood of a lifetime of comparative anonymity and hard slog without the comforting sense of an elevated identity. How many in the arts want to admit that one of the main rewards is a sense of superiority, a perverse high status particularly when it comes with added political frisson of being seen as a political artist? Producing real cultural change can be a lot harder, lonelier and less rewarding.

More images:

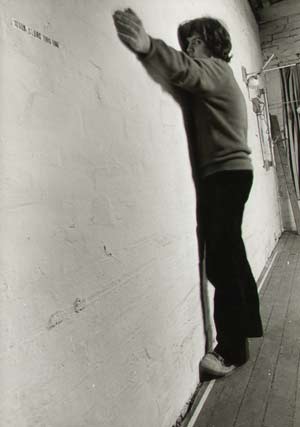

Walk Along This Line 1970, an early audience participatory work

by Ian Milliss

Federated Miscellaneous Workers Union monthly magazine 1991

edited by Ian Milliss

Ian Milliss Adapted Popeye T Shirt 2010